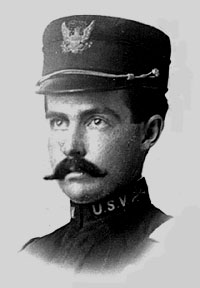

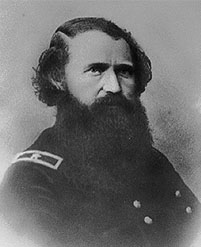

On the 4th day of August, 1862, Captain James M. Williams, Co. F, 5th Kansas Cavalry, was appointed by Hon. Jas. H. Lane Recruiting Commission for that portion of Kansas lying north of the Kansas River, for the purpose of recruiting and organizing a regiment of infantry for the U.S. service, to be composed of men of African descent. He immediately commenced the work of recruiting by securing the muster-in of recruiting officers with the rank of 2d Lieutenant, and by procuring supplies from the Ordanance, Quartermaster and Commissary departments, and by establishing in the vicinity of Leavenworth a camp of rendezvous and instruction.

Captain H.C. Seaman was about the same time commissioned with like authority for that portion of Kansas lying south of the Kansas River. The work of recruiting went forward with rapidity, the intelligent portion of the colored people entering into the work heartily, and evincing by their actions a willing readiness to link their future and share the perils with their white brethren in the war of the rebellion, which then waged with such violence as to seriously threaten the nationality and life of the Republic.

Within sixty days, 500 men were recruited and placed in camp, and a request made that a battalion be mustered into the U.S. service. This request was not complied with, and the reasons assigned were wholly unsatisfactory, yet accompanied with assurances of such a nature as to warrant the belief that but a short time would elapse ere the request would be complied with.

In the meantime complications with the civil authorities in the Northern District had arisen, which at one time threatened serious results. These complications originated from the following causes, each affecting different classes:

First, an active sympathy for the rebellion; second, an intolerant prejudice against the colored race, which would deny them the honorable position in society which every soldier is entitled to, even though he gained that position at the risk of his life in the cause of the nation, which could ill afford to refuse genuine sympathy and support from any quarter. Third, on the part of a few genuine loyalists, who believed that this attempt to enlist colored men would not be approved by the War Department, and that the true interests of the colored man demanded that their time should not be vainly spent in the effort. Lastly, large class who believed that the negro did not possess the necessary qualifications to make efficient soldiers, and that consequently the experiment would result in defeat, disaster and disgrace.

Col. William, acting under the orders of his military superiors, felt that it was no part of his duty to take counsel of any or all of these classes. He saw no course for him to pursue but to follow his instructions to the letter. Consequently, when the civil authorities placed themselves in direct opposition to those of the military, by arresting and confining the men of the command on the most frivolous charges and indicting their commanders for crime, such as unlawfully restraining persons of their liberty, etc., by enforcing proper military discipline, he ignored the right of the civil authorities to interfere with his military actions in a military capacity and under proper authority.

All the classes above enumerated joined in this opposition, which, if successful, could only have inured to the interests of those persons properly coming under the head of the 1st class enumerated or mentioned. The result has undeceived those persons who acted from honest convictions embraced in the 3d and 4th classes, and to the other two classes no apologies are necessary nor intended.

On the 28th of October, 1862, a command, consisting of detachments from Capt. Seaman’s and Capt. Williams’ recruits, were moved and camped near Butler. This command–about 225 men, under Capt. Seaman–was attacked by a rebel force of about 500, commanded by Col. Cockrell, but after a severe engagement the enemy was defeated with considerable loss. Our loss was 10 killed and 12 wounded, including Capt. A.J. Crew among the first mentioned, a gallant young officer. The next morning the command was reinforced by a few recruits under command of Capt. J.M. Williams, and pursued the enemy a considerable distance, but without further action. This is supposed to have been the first engagement in the war in which colored troops were engaged.

The work of recruiting , drilling and discillining the regiment was continued under these adverse circumstances until the 13th of January, 1863, when a battalion of six companies, formed by the consolidation of Col. Williams’ recruits with those of Capt. Seaman, was mustered into the U.S. service by Lieut. Sabin of the regular army. Between January 13th and May 2d, 1863, the other four companies were organized, when the regimental organization was completed, as will appear by the muster-in rolls of the regiment.

Immediately, after it organization the regiment was ordered to Baxter Springs, where it arrived in May, 1863, and the work of drilling the regiment was vigorously prosecuted.

Parts of two companies of the regiment, and a small detachment of cavalry and one piece of artillery, made a diversion on Shawnee, Mo., attacked and dispersed a small rebel force and captured five prisoners.

While encamped here, on the 18th of May, a foraging party, consisting of 25 men from this regiment and 20 men of the 2d Kansas Battery, Maj. R.G. Ward commanding, was sent into Jasper county, Missouri. This party was suprised and attacked by a force of 300 rebels commanded by Major Livingstone, and defeated, with a loss of 16 killed and five prisoners, three of which belonged to the 2d Kansas Battery and two to this regiment. The men of the 2d Kansas Battery were afterwards exchanged under a flag of truce for a like number of prisoners captured by this regiment. Livingstone refused to exchange the colored prisoners in his possession, and gave as his excuse that he should hold them subject to the orders of the rebel War Department. Shortly after this Colonel Williams received information that one of the prisoners held by Livingstone had been murdered by the enemy. He immediately sent a flag of truce to Livingstone demanded the body of the person who committed the barbarous act. Receiving an envious and unsatisfactory reply, Colonel Williams determined to convince the rebel commander that that was a game at which two could play and directed that one of the prisoners in his possession be shot, and within 30 minutes the order was executed.

He immediately informed Major Livingstone of his action, sending the information by the same party that brought the dispatch to him. Suffice it to say that this ended the barbarous practice of murdering prisoners of war, so far as Livingstone’s command was concerned.

Colonel Williams says: “I visited the scene of this engagement the morning after its occurance and for the first time beheld the horrible evidences of the demoniac spirit of these rebel fiends in their treatment of our dead and wounded. Men were found with their brains beaten out with clubs, and the bloddy weapons left by their sides, and their bodies most horribly mutilated.”

It was afterwards ascertained that the force who attacked this foraging party consisted partially of citizens of the neighborhood, who, while enjoying the protection of our armies, had collected together to assist the rebel forces in this attack. Colonel Williams directed that the region of country within a radius of five miles from the scene of conflict should be devastated, and is of opinion that this effectually prevented a like occurance in the same neighborhood.

Subsequently, while on this expedition, the command captured a prisoner in arms who had upon his person the evidence of having been paroled by the commanding officer at Fort Scott, Kansas, who was shot on the spot.

The regiment remained in camp at Baxter Springs until the 27th of June, 1863, when it struck tents and marched for Fort Gibson in connection with a large supply train from Fort Scott en route to the former place.

Colonel Williams had received information that satisfied him that the train would be attacked in the neighborhood of Cabin Creek, Cherokee Nation. He communicated this information to Lieut. Colonel Dodd, of the 2d Colorado Infantry, who was in command of the escort, and volunteered to move his regiment in such manner as would be serviceable in case the expected attack should be made. The escort proper to the train consisted of six companies of the 2d Colorado Infantry, a detachment of three companies of cavalry from the 6th and 9th Kansas, and one section of the 2d Kansas Battery. This force was joined, on the 28th of June, by three hundred men from the Indian Brigade, commanded by Major Foreman, making altogether a force of about eight hundred effective men.

On arriving at Cabin Creek, July 1st, 1863, the rebels were met in force–about twenty-two hundred strong–under command of Gen. Cooper. Some skirmishing occurred on that day, when it was ascertained that the enemy occupied a strong position on the south bank of the Creek, and upon trial it was found that the stream was not then fordable for infantry, on account of a recent shower; but it was supposed that the swollen current would have sufficiently subsided by the next morning to allow the infantry to cross. The regiment then took a strong position on the north side of the stream and camped for the night. After a consultation of officers, it was agreed that the train should be parked in the open prairie and guarded by three companies of the 2d Colorado and a detachment of one hundred men of the 1st Colored, and that the balance of the troops, Col. Williams commanding, should engage the enemy and drive him from his position.

Accordingly, the next morning, July 2, 1863, the command moved, which consisted of the 1st Kansas Volunteer Colored Infantry, three companies of the 2d Colorado Infantry, commanded by the gallant Major Smith of that regiment, the detachments of cavalry and Indian troops before mentioned and four pieces of artillery, making altogether a force of about twelve hundred men.

With this force, after an engagement of two hours duration, the enemy was dislodged and driven from his position in great disorder, with a loss of one hundred killed and wounded and eight prisoners. The loss on our side was eight killed and twenty-five wounded, including Maj. Foreman, who was shot from his horse while attempting to lead his men across the creek under the fire of the enemy, and Capt. Ethan Earl, of the 1st Colored, who was wounded at the head of his company.

This engagement was the first during the war in which white and colored troops were joined in action, and to the honor and credit of the officers and men of Col. Dodd’s command be it said they allowed no prejudice on account of color to interfere in the discharge of their duty in the face of the enemy alike to both races.

This was the first battle in which the whole regiment had been engaged, and here they evinced a coolness and true soldierly spirit which inspired the officers in command with that confidence which subsequent battle scenes satisfactorily proved was not unfounded.

The road now being open, the entire command proceeded to Fort Gibson, where it arrived on the evening of the 5th of July, 1863. On the 16th of July the entire force at Fort Gibson, under command of Gen. Blunt, moved upon the enemy, about six thousand strong, commanded by Gen. Cooper, and encamped at Honey Springs, twenty miles south of Fort Gibson. Our forces came upon the enemy on the morning of the 17th of July, and after a sharp and bloody engagement of two hours duration, the enemy was totally defeated, with a loss of four hundred killed and wounded and one hundred prisoners.

At the height of the engagement, Gen. Blunt ordered Colonel Williams to move his regiment against that portion of the enemy’s line held by the 29th and 30th Texas regiments and a rebel battery, with directions to charge them if he thought he could carry and hold the position. The regiment was moved at a shoulder arms, pieces loaded and bayonets fixed, under a sharp fire, to within forty paces of the rebel lines, without firing a shot. The regiment then halted and poured into their ranks a well-directed volley of “buck and ball” from the entire line, such as to throw them into perfect confusion, from which they could not immediately recover. Col. Williams’ intention was after the delivery of this volley, to charge their line and capture their battery, which the effect of this volley had doubtless rendered it possible for him to accomplish. But he was at that instant rendered insensible from gunshot wounds, and the next officer in rank, Lieut. Col. Bowles, not being aware of his intentions, the project was not fully carried out. Had the movement been made as contemplated, the entire rebel line must have been captured. As it was, most of the enemy escaped, receiving a lesson, however, which taught them not to despise on the battle field the race they had long tyrannized over as having “no rights which a white man was bound to respect”.

Col. Williams says; “I had long been of the opinion that this race had a right to kill rebels, and this day proved their capacity for the work. Forty prisoners and one battle flag fell into the hands of my regiment on this field”.

The loss to the regiment in this engagement was five killed and thirty-two wounded. After this, the regiment returned to Fort Gibson and went into camp, where it remained until the month of September, when it again moved with the Division against the rebel force under General Cooper, who fled at our approach.

After a pursuit on one hundred miles, and across the Canadian River to Perryville, in the Choctaw Nation, all hopes of bringing them to an engagement was abandoned, and the command returned to camp on the site of the rebel Fort Davis, situated on the south side of the Arkansas River, near its junction with Grand River.

The regiment remained in this camp, doing but little duty, until October, when orders were received to proceed to Fort Smith, where it arrived during the same month. At this point it remained until December 1st, making a march to Waldron and returning via Roseville, Arkansas, and in the same month went into winter quarters at the latter place, situated fifty miles east of Fort Smith on the Arkansas River.

The regiment remained at Roseville until March, 1864, when the command moved to join the forces of General Steele, then about starting on what was known as the Camden Expedition. Joining General Steele’s command at the Little Missouri River, distant twenty-two miles northeast of Washington, Arkansas, the entire command moved upon the enemy, posted on the west of Prairie de Anne, and within fifteen miles of Washington. The enemy fled, and our forces occupied their works without an engagement.

The pursuit of the enemy in this direction was abandoned, and the command marched upon Camden via the Washington and Camden road, which was struck as Moscow, distant five miles from the works abandoned by the enemy. At this point, the Division, commanded by Gen. Thayer, was attacked in the rear by a larger force of the enemy, but after a spirited engagement of an hour’s duration, they were effectually repulsed, the regiment sustaining no loss in the action.

The command arrived at Camden on the 16th of April, 1864, and occupied the place with its strong fortifications without opposition. On the day following Col. Williams started with five hundred men of the 1st Colored, two hundred Cavalry, detailed from the 2d, 6th and 14th Kansas regiments and one section of the 2d Indiana Battery, with a train to load forage and provisions at a point twenty miles west of Camden, on the Washington road. On the 17th he reached the place and succeeded in loading about two-thirds of the train, which consisted of two hundred wagons. At dawn of the 18th the command moved towards Camden, and loaded the balance of the wagons from the plantations by the way side. At a point fourteen miles west of Camden the advance encountered a small force of the enemy, who, after slight skirmishing, retreated down the road in such a manner as to lead Col. Williams to suspect that this movement was a feint intended to cover other movements or to draw the command into an ambuscade.

Just previous to this he had been reinforced by a detachment of three hundred men of the 18th Iowa Infantry, and one hundred additional cavalry, commanded by Capt. Duncan, of the 18th Iowa.

In order to prevent any surprise, all detached foraging parties were called in, and the original command placed in the advance, leaving the rear in charge of Capt. Duncan’s command, with orders to keep flankers well out and to guard cautiously against a surprise. Col. Williams at the front, with skirmishers and flankers well out, advanced cautiously to a point about one and a half miles distant, sometimes called Cross Roads, but more generally known as Poison Springs, where he came upon a skirmish line of the enemy, which tended to confirm his previous suspicion of the character and purpose of the enemy. He therefore closed up the train as well as was possible in this thickly timbered region, and made the necessary preparation for fighting. He directed the cavalry, under Lieut. Henderson, of the 6th, and Mitchell, of the 2d, to charge and penetrate the rebel line of skirmishers in order to develop their strength and intentions. The movement succeeded most admirably in its purposes, and the development was such that convinced Col. Williams that he had before him a struggle of no ordinary magnitude.

The cavalry, after penetrating the skirmish line, came upon a strong force of the enemy, who repulsed and forced them back to their original line, not, however, without hard fighting and severe loss on our part in killed and wounded, including in the latter the gallant Lieut. Henderson, who afterwards fell into the hands of the enemy.

The enemy now opened on our lines with ten pieces of artillery–six in front and four on the right flank. From a prisoner, Col. Williams learned that the force of the enemy was from eight to ten thousand, commanded by Gens. Price and Maxey. These developments and this information convinced him that he could not hope to defeat the enemy; but as there was no way to escape with the train except through their lines, and as the train and its contents were indispensable to the very existence of our forces at Camden, who were then out of provisions, he deemed it his duty to defend the train to the last extremity, hoping that our forces at Camden, on learning of the engagement, would attack the enemy in his rear, thus relieving his command and saving the train.

With this determination, he fought the enemy’s entire force from 10 a.m. until 2 p.m., repulsing three successive assaults, and inflicting upon the enemy severe loss.

Col. Williams says; “The conflict during these four hours was the most terrific and deadly in its character of any that has ever fallen under my observation.”

At 2 p.m. nearly one-half of our force engaged had been placed hors de combat, and the remainder were out of ammunition. No supplies arriving, the Col. was reluctantly compelled to abandon the train to the enemy and save as much of the command as possible by taking to the swamps and cane-breaks and making for Camden by a circuitous route, thereby preventing pursuit by cavalry. In this manner most of the command that was not disabled in the field reached Camden during the night of the 18th. For a more specific and statistical report of this action, in which the loss to the First Colored alone was 187 men and officers, the official report of Colonel J. M. Williams is herewith submitted:

Camden, Arkansas, April 24, 1864

Captain–I have the honor to submit the following report of a foraging expedition under my command. In obedience to verbal orders received from Brigadier General Thayer, I left Camden, Arkansas, on the 11th instant with the following forces, viz.;

Five hundred of the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry, commanded by Major Ward.

Fifty of the 6th Kansas Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Henderson.

Seventy-five of the 2d Kansas Cavalry, commanded by Lieut. Mitchell.

Seventy of the 14th Kansas Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Utt.

One section of the 2d Indiana Battery, under Lieutenant Haynes.

In all, 695 men and two guns, with a forage train of 198 wagons.

I proceeded westerly on the Washington road a distance of eighteen miles, where I halted the train and dispatched part of it in different directions to load, one hundred wagons with a large part of the command, under Major Ward, being sent six miles beyond the camp. These wagons returned to camp at midnight, nearly all loaded with corn.

At sunrise on the 18th, the command started on the return, loading the balance of the train as it proceeded, there being few wagon loads of corn to be found at any one place. I was obliged to detail portions of the command in different directions to load the wagons, until nearly all of my available force was so employed.

At a point known as Cross Roads, four miles west of my camping ground, I was met by a reinforcement of three hundred and seventy-five men of the 6th Kansas, Lt. Phillips commanding, forty-five men of the 2d Kansas Cavalry, Lieut Ross commanding, twenty men of the 14th Kansas Cavalry, Lt. Smith commanding, and two mountain howitzers from the 6th Kansas Cavalry, Lieut. Walker commanding–in all 465 men and two mountain howitzers. These, added to my former command, made my entire force consist of eight hundred and seventy-five infantry, two hundred and eighty-five cavalry and four guns. But the excessive fatigue of the preceding day, coming as it did at the close of a toilsome march of twenty-four hours without halting, had so affected the infantry that fully one hundred of the 1st Kansas Colored were rendered unfit for duty. Many of the cavalry had, in violation of orders, straggled from their commands, so that at this time my effective force did not exceed one thousand men.

At a point one mile east of this, my advance came upon a picket of the enemy, which was driven back one mile, when a line of the enemy’s skirmishers presented itself. Here I halted the train, formed a line of the small force I then had in advance, and ordered that portion of the 1st Kansas Colored which had previously been guarding the rear of the train to the front, and gave orders for the train to be parked as closely as the nature of the ground would permit. I also opened a fire upon the enemy’s line from the section of the 2d Indiana Battery, for the double purpose of ascertaining, if possible, if the enemy had artillery in position in front, and also to draw in some foraging parties which had previously been dispatched upon either flank of the train. No response was elicited save a brisk fire from the enemy’s skirmishers.

Meanwhile, the remainder of the 1st Kansas Colored had come to the front, as also three detachments of cavalry, which formed part of the original escort, which I formed in line facing to the front, with a detachment of the 14th Kansas Cavalry on my right, and detachments of the 2d and 6th Kansas Cavalry on the left flank. I also sent orders to Capt. Duncan, commanding the 18th Iowa Infantry, to so dispose of his regiment and the cavalry and howitzers which came out with him as to protect the rear of the train, and to keep a sharp lookout for a movement upon his rear and right flank.

Meanwhile, a movement of the enemy’s infantry towards my right flank had been observed through the thick brush which covered the face of the country in that direction. Seeing this, I ordered forward the cavalry on my right, under Lieuts. Mitchell and Henderson, with orders to press the enemy’s line, force it if possible, and at all events to ascertain his position and strength, fearing as I did that the silence of the enemy in front was but for the purpose of drawing me on to the open ground which lay in my front. At this juncture, a rebel rode into my lines and inquired for Col. De Morse. From him I learned that General Price was in command of the rebel force, and that Col. De Morse was in command of the force on my right.

The cavalry had advanced but four hundred yards, when a brisk fire of musketry was opened upon then from the brush, which they returned with true gallantry, but were forced to fall back. In this skirmish many of the cavalry were unhorsed, and Lieut. Henderson, of the 6th Kansas Cavalry, fell, wounded in the abdomen, while bravely and gallantly urging his command forward.

In the meantime, I formed five companies of the 1st Kansas Colored, with one piece of artillery, on my right flank, and ordered up to their assistance four companies of the 18th Iowa Infantry. Soon my orderly returned from the rear with a message from Capt. Duncan, stating that he was so closely pressed in the rear by the enemy’s infantry and artillery that the men could not be spared.

At this point, the enemy opened on me with two batteries–one, of six pieces, in front, and one, of three pieces, on my right flank–pouring in an incessant and well-directed cross fire of shot and shell. At the same time he advanced his infantry both in front and on my right flank.

From the force of the enemy–now for the first time made visible–I saw that I could not hope to defeat him, but still resolved to defend the train to the last, hoping that reinforcements would come up from Camden.

I suffered them to approach within one hundred yards of my line, when I opened upon them with musketry charged with buck and ball, and after a contest of fifteen minutes duration, compelled them to fall back. Two fresh regiments coming up, they again rallied and advanced upon my line, this time with colors flying and continuous cheering, so loud as to drown even the roar of musketry. Again I suffered them to approach even nearer than before, and opened upon them with buck and ball, their artillery still pouring in a cross fire of shot and shell over the heads of their infantry, and mine replying with vigor and effect. And thus, for another quarter of an hour, the battle was waged in a desperate fury. The noise and din of this almost hand-to-hand conflict was the loudest and most terrific it has ever been my lot to listen to. Again they were forced to fall back, and twice during this contest were their colors brought to the ground, but as often raised.

During these engagements fully one-half of my infantry engaged were either killed or wounded. Three companies were left without any officers and seeing the enemy again reinforced with fresh troops, it became evident that I could hold my line but little longer. I now directed Maj. Ward to hold the line until I could ride back and form the 18th Iowa in proper shape to support the retreat of the advanced line.

Meanwhile, so many of the gunners having been shot from around their pieces as to leave too few men to serve the guns, I ordered them to retire to the rear of the train and report to the cavalry officer there. Just as I was starting for the line of the 18th Iowa my horse was shot, which delayed me until another could be procured, when I rode to the rear and formed a line of battle facing in the direction the enemy was advancing.

Again did the enemy hurl his columns against the remnant of men that formed my front and right flank, and again were they met as gallantly as before. But my decimated ranks were unable to resist the overpowering force hurled against them, and after their advance had been checked, seeing that our lines were completely flanked on both sides, Maj. Ward gave the order to retire, which was done in good order, forming and charging the enemy twice before reaching the rear of the train.

With the assistance of Maj. Ward and other officers, I succeeded in forming a portion of the 1st Kansas Colored in rear of the 18th Iowa, and when the enemy approached this line, they gallantly advanced to the line of the 18th and with them poured in their fire. The 18th maintained their line manfully, and stoutly contested the ground until nearly surrounded, when they retired, and forming again, checked the advancing foe, and still held their ground until again nearly surrounded, when they again retired across a ravine which was impassable for artillery, and I gave the orders for the piece to be spiked and abandoned.

After crossing this ravine I succeeded in forming a portion of the cavalry which I kept in line in order to give the infantry time to cross the swamp, which lay in our front, which they succeeded in doing. By this means nearly all, except the badly wounded were enabled to reach camp. Many wounded men belonging to the 1st Kansas Colored fell into the hands of the enemy, and I have the most positive assurances from eye witnesses that they were murdered on the spot. I was forced to abandon everything to the enemy, and they thereby became possessed of the large train.

With two six pounder guns and two twelve pounder mountain howitzers, together with what force could be collected, I made my way to this post, where I arrived at 11 p.m. of the same day.

At no time during the engagement, such was the nature of the ground and the size of the train, was I obliged to employ more than five hundred men and two guns to repel the assaults of the enemy, whose force, from the statements of prisoners, I estimate at ten thousand men and twelve guns. The columns of assault which were thrown against my front and right flank consisted of five regiments of infantry and one of cavalry, supported by a strong force which operated against my left flank and rear. My loss, in killed, wounded and missing during this engagement was as follows;

Killed–Ninety-two.

Wounded–Ninety-seven.

Missing–On hundred and six.

Very respectfully, etc.,

J. M. WILLIAMS

Colonel 1st Kansas Colored Vol. Inf.,

commanding expedition.

Captain Wm. S. Whitten, Assistant Adjutant General.

I will simply say that in this action, although defeated and driven from the field with great loss, the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry brought no stain of dishonor upon the State it represented, but in my opinion added other laurels to the wreath of glory and honor which her sons have woven from the hard-earned garlands of many well-contested battle fields during the war of the great rebellion.

On the 26th day of April following Gen. Steele’s command evacuated Camden and marched for Little Rock. At Saline Crossing, on the 30th of April, the rear of Gen. Steele’s command was attacked by the entire force of the enemy, commanded by Gen. Kirby Smith. The engagement which followed resulted in the complete defeat of the enemy, with great loss on his part. In this engagement the 1st Kansas Colored was not an active participant, being at the moment of the attack in the advance, distant five miles from the rear and scene of the engagement. The regiment was ordered back to participate in the battle, but did not arrive on the line until after the repulse of the enemy and his retirement from the field.

On the day following, May 1st, 1864, Colonel Williams was ordered to take command of the 2d Brigade, Frontier Division, 7th Army Corp., and never afterwards resumed direct command of his regiment. It constituted for the most of the time, however, a part of the Brigade which he commanded until he was mustered out of service with the regiment.

The regiment remained with its Division at Little Rock until some time during the month of May, when it marched for Fort Smith–then threatened by the enemy–at which point it arrived during the same month. This campaign was one of great fatigue and privation, and accomplished only with great loss of life and material, with no adequate recompense or advantage gained.

The regiment remained on duty at Fort Smith until January 16th, 1865, doing heavy escort and fatigue duty. On the 16th of September, 1864, a detachment of forty-two men of Co. K, commanded by Lieut.. D. M. Sutherland, while guarding a hay-making party near Fort Gibson, were surprised and attacked by a large force of rebels under Gen. Gano and defeated, after a gallant resistance, with a loss of twenty-two killed and ten prisoners–among the latter the Lieutenant commanding.

On the 16th of January 1865, the regiment moved to Little Rock, where it arrived on the 31st of the same month, where it remained on duty until July, 1865, when it was ordered to Pine Bluffs, Ark. Here it remained, doing garrison and escort duty, until October 1st, 1865, when it was mustered out of service and ordered to Fort Leavenworth for final payment and discharge. The regiment received its final payment and was discharged at Fort Leavenworth on the 30th day of October, 1865.

Upon referring to the reports of the campaigns and battles in which this regiment was engaged, it will be evident to the reader that they neither shrank from any duty nor avoided and peril. On the contrary, it will ever be a source of gratification to the Colonel commanding to have been connected with a regiment that performed its full share of duty, and offered up, in defense of the liberties of the nation, its full share of patriotic lives, laid upon the alter of freedom for the benefit of the present and future generations, again reunited and cemented with the blood of patriots, never to be dismembered by traitors without or foes within.

Citizenship in a free country amply rewards the war-worn soldier, who hails with joy the advent of peace, and turns with alacrity from the “pomp and circumstance of glorious war,” once more to engage in those more congenial pursuits incident to a time of tranquillity and peace.

(SOURCE: Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Kansas, 1861-’65. Topeka, Kansas: 1896 reprint. Transcription provided by Dale Vaughn, Civil War Roundtable of Eastern Kansas.)

The negro regiment has a successful engagement with guerillas – Capt. Andrew I. Crew killed – Bravery of the black soldiers

HEADQUARTERS 1ST REG’T KANSAS COLORED

VOL.’S, FORT AFRICA, ON THE OSAGE NEAR

BUTLER, BATES CO., Oct. 30, 1862.

A detachment of seventy men from the southern battalion, (Col. Seaman’s,) and one hundred and sixty from Col. Williams, the latter undet Capt. R. G. Ward, Company B; the entire detachment under Col. Seaman, who acted under instructions from Maj. Henning, arrived at this point on Tuesday afternoon, having left Fort Lincoln late on Monday. The enemy’s scouts were seen in force when we arrived at this point, the residence of an infamous guerilla named Toothman, whose son is now a prisoner at Frot Lincoln. We were aiming to clean out a rendevous near here, on what is known as the Island, a long marshy tract of land, lying in the Osage, which been the resort of the Jackman and Cockerill bushwhackers. We found the latter in force, with a splendidly armed and mounted body, variously estimated at from 400 to 800 men. The probability is that the first named was the correct estimate, but since our arrival he has been reinforced till his command numbers over 600. We encamped within Toothman’s yard, throwing up a rail barricade and raising a flag. We named the place “Fort Africa.” Sending back for cavalry and for the balance of the regiment, we skirmished two days. Yesterday morning our skirmishers shot two scouts. After dinner, the enemy succeeded in drawing out a small detachment and cutting it off from our main body. A sharp engagement ensued, in the attempt to rescue our detachment. We lost eight men killed, and ten wounded. Capt. Crew, Company A, 1st Reg. K. C. V., formerly of the Mansion House, was killed. Lieut. Joseph Gardner was severely wounded, but he will be well within a week or two. The enemy report fifteen killed this morning and must have as many more wounded.

It is useless to talk any more of negro courage. The men fought like tigers, each and every one of them, and the main difficulty was to hold them well in hand.

We have just received reinforcements, and have intelligence of a guerrilla force that renders a movement necessary. Saddle and mount is the word. There are the boys to clean out the bushwhackers.

Richard J. Hinton

Lieut. Joseph Lyon arrived here on Sunday with the body of Capt. Crew. He was in the engagement, and fully confirms the report of our correspondent.

Capt. Crew had a wound through the heart and one through the groin and died instantly. His watch, which was stolen from him on the field, was afterwards found on the body of a bushwhacker, undoubtedly the man who had killed Capt. Crew, was another instance of speedy and retributive justice. Lt. Lyon says Missouri guerrillas have the highest respect for black valor.–ED.

(Source: Leavenworth, Kansas Daily Conservative, 4 November 1862. Transcribed by Bryce Benedict.)

Kansas black soldiers battle! They fight bravely – List of killed and wounded

[Correspondence of the Lawrence Republican,

TOOTHMAN’S MOUND, BATES CO., MO.]

NOVEMBER 1, 1862.

EDITOR REPUBLICAN: You have doubtless heard, ere this, of the battle of Toothman’s Mound fought here on the 29th of last month. Yet, a few particulars may not be uninteresting.

There is a strip of land between the Marais des Cygnes, and a long connecting slough, known as “The Island.” This has long been infested with more or less bushwhackers, who have carried all their plunder off to it for safekeeping. Lately, they have been increasing in strength and boldness, until they had become the terror of all good citizens for miles around. Accordingly, about the 25th of last month, Col. Seaman was ordered, with about one hundred men, to proceed to the Island. He was joined by about one hundred and fifty men, under Capt. Ward (commanding in the absence of Col. Williams), and acting in concert, they moved down to this point, where they stopped within about three miles of the Island, and in sight of the enemy.

About 250 of our Regiment were left in at Fort Lincoln, myself among the number. The day after the expedition left, we received a dispatch from Capt. Ward, calling for reinforcements. With three rounds of ammunition each (all we had in camp) we started for the scene of action–a little over one hundred of us, all told. We marched night and day until we joined our boys. And when we came up with them on the evening of the 28th, you may but slightly imagine our consternation, when you know that we found eight of our brave men dead, and eleven severely wounded. Among the former, the gallant Capt. Crew, of Leavenworth, and among the latter, Lieut. Joseph Gardner, well known by most of your citizens. He was wounded in the head, the hip and the knee, besides a ball grazed his ankle and one foot. For the benefit of their friends, I will give a list of the killed and wounded; most of the former were from Topeka:

KILLED.–Capt. Crew, Co. A; Corp. Joseph Talbot; Privates Thomas Lane, Marion Barber, Allen Rhodes, Henry Gash, all of Co. F; John Sixkiller, Seaman’s Battalion.

WOUNDED.–Lieut. Joseph Gardner, Co. F, head, hip and knee; Private Thos. Knight, both legs; Geo. Dudley, both legs; Manuel Dobson, both arms; Lazarus Johnston, arm, all of Co. F; Serg’t Edward Lowery, Seaman’s battalion, shoulder and arm; Serg’t Shelley Banning, Seaman’s Battalion, right breast and hip; Corp’ls Andy Hytower, left shoulder; Anderson Riley, left shoulder; Private Ed. Curtis, back and mouth, all of Seaman’s battalion; Corp’l Jacob Edwards, Co. E, head and side.

The wounded are doing well . . . [several sentences missing here ] . . . who charged upon them desperately, and hewed them down in a horrible manner, not, however, without a heavy loss on their side. Our men, after the first fire, had to resort to the bayonet, which proved very effective. The officers were armed with revolvers and sabers, and they used these well, except Lieut. Gardner, who was one of the first to fall, and consequently did not get many shots at the enemy. Capt. Crew was called upon to surrender; he bravely replied–”Never”–and died with that determination. The only officer now left was Lieut. Huddleston, who had also determined to prefer death to being taken. You may well imagine his situation. The only remaining white man, of course the fury of the enemy was chiefly directed to him, but he kept the enemy at bay until succor reached him. He never discharged his revolver without taking good aim and doing good execution. In the meantime most of the available men in camp were ordered out under Capt. Armstrong and Lieut. Thrasher. They brought up their men in two bodies at right angles, and delivered a few volleys at the enemy, cross-fire, which caused him to retreat in great haste. He carried his wounded with him, and as the wind was toward us, fired the prairie, making it difficult to save the wounded alone, and consequently scorching the bodies of some of our dead.

The whole force of the enemy was commanded by Cockerel, and numbered about five hundred. The day after we came up with reinforcements, the enemy retreated toward the southeast, leaving some valuable horses and beef cattle, which fell into our hands.

Col. Williams arrived yesterday. Having proven that black men can fight, we are now prepared to scour this country thoroughly, and not leave a place where a traitor can find refuge.

Yours, in haste, W. H. Smallwood

(Source: Lawrence Republican, 6 November 1862. Transcribed by Bryce Benedict.)

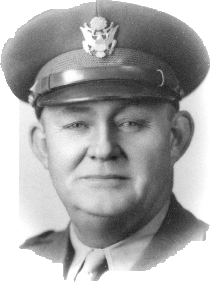

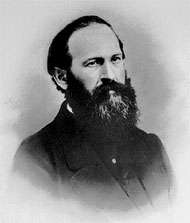

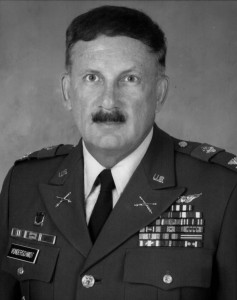

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law.

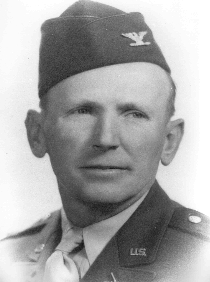

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law. Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968.

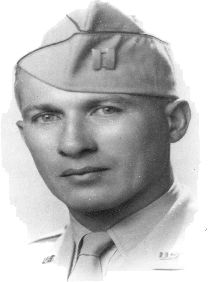

Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968. CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist.

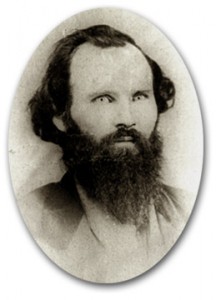

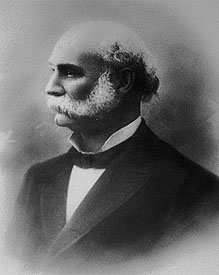

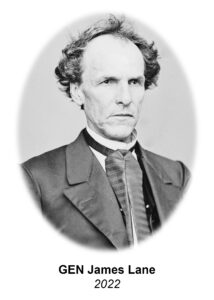

CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist. General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas.

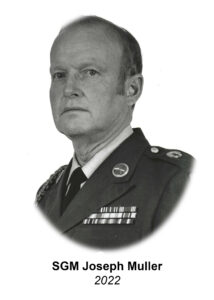

General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas. Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years.

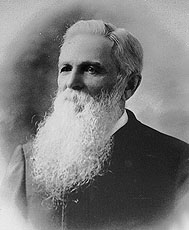

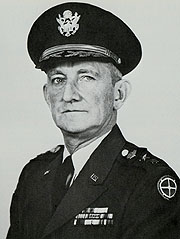

Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years. Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas.

Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas. Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital. Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.