Made with by Graphene Themes.

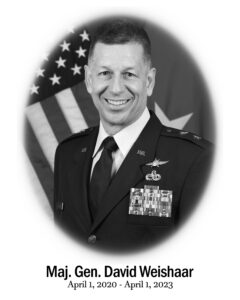

Maj Gen David Weishaar

Maj Gen David Weishaar

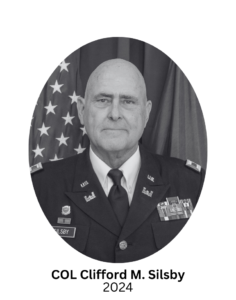

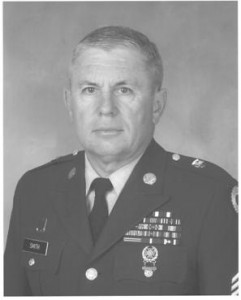

COL Clifford M. Silsby was born on July 19, 1952 in Concordia, Kanas. He enlisted in the Kansas Army National Guard after high school graduation in February, 1970. He completed Basic and Advanced Individual training at Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri. He started his military career as an Engineer Equipment Operator with the 891st Engineer Battalion and 891st Engineer Company in Mankato, Kansas, followed by assignments with the 170th Maintenance Company. He graduated from the Kansas National Guard Officer Candidate School. During the period of 1984-1992 he held many positions as a Company Grade Officer with Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 891st Engineer Battalion in Iola, Kansas.

He quickly rose through the ranks with promotion to Lieutenant Colonel in 1996 while assigned to the 69th Troop Command, holding several positions. He served as Commander, 89lst Engineer Battalion, as Surface Maintenance Manager for the Kansas Army National Guard, as Executive Officer of the 2d Bn, 235th Regiment, and as Commander, Kansas Regional Training Center, Salina, Kansas. He served as Director of Installations for Joint Force Headquarters from 2005 to 2012. In 2012 COL Silsby was assigned to Operation Enduring Freedom on Active Duty as Officer in Charge of the Special Collections Office, Center for Army Lessons Learned, Ft. Leavenworth, in Afghanistan. Colonel Silsby retired in 2012.

During COL Silsby’s long career he received numerous awards and decorations, including the Legion of Merit, the Meritorious Service Medal with Silver Oak Leaf Cluster, the Army Commendation Medal with 4 Bronze Oak Leaf Clusters, the Army Achievement Medal with 3 Bronze Oak Leaf Clusters, the Army Reserve Components Achievement Medal, National Defense Service Medal, Afghanistan Campaign Medal with Campaign Star, Armed Forces Reserve Medal with Silver Hourglass, Global War on Terrorism Medal, NCO Professional Development Ribbon, Army Service Medal, NATO Medal, Army Superior Unit Award, Kansas National Guard Service Medal, and Kansas Emergency Duty Service Ribbon.. In addition, he received the Kansas National Guard Medal of Excellence and has been inducted into the Kansas Army National Guard Officer Candidate School Hall of Fame. He was also the recipient of several additional special honors.

Over the course of his military career Colonel Silsby completed over twenty schools and courses. He also has a Bachelor of Science in Organizational Management and Business from Friends University, Wichita, Kansas, and a Master of Strategic Studies from the United States Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, PA. He is a graduate of the U. S. Army War College.

A few of his special military service accomplishments were as a Kansas member and manager of the U. S. Army Installations Sustainment and Maintenance Program (ISM), manager of the RETRO Europe Maintenance Program, co-author of the Kansas Advanced Turbine Engineer Program, and Chairman (2008-09) and member of the National Guard Bureau Facilities and Engineering Advisory Council (2006-2009).

In addition to Colonel Silsby’s outstanding military career, he also volunteered with multiple organizations. He served as Chairman of the Jewell County Industrial Development Association and was a volunteer firefighter in Mankato, Kansas. He served as a life member of both NGAUS and NGAKS and has served for 30 years on the Board of Directors of the Museum of the Kansas National Guard. He has been an active member of the Kansas Antique Steam Show Safety Association, holding several board positions. He has been an active member of the Jewell County Historical Society and has served with two American Legion Posts.

He is married to Susan Silsby, and they have five children: Krista (Ben) Ruthstrum, Angela (Timothy) Brown, Elizabeth (Andrew) Stratman, Jennifer, and SFC James (Karla) Silsby. They also have ten grandchildren.

Col Edward L. Sykes was born on June 15, 1943 in Rice Lake, Wisconsin. He graduated from Caldwell County High School, Princeton, Kentucky, in 1962. He attended the university of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering in 1967.

He was commissioned in 1967 from the University of Wisconsin AF ROTC program, with his first assignment to attend undergraduate pilot training at Reese AFB in Texas. He next assignment was to McConnell AFB, Wichita, Kansas, flying F-105 Thunderchiefs. He was then assigned to Korat Royal Thai Air Base, where he successfully completed 118 combat missions over the jungles of Vietnam and Southeast Asia in the F-105 Thunderchief.

Following his combat tour, he went back to Reese AFB, Texas, where he served as a T-37 instructor. In 1972 he joined the 184th Tactical Fighter Group (TFG), Kansas Air National Guard, as an F-105 instructor pilot. He soon became the Chief of Academic Training, where he wrote several training manuals for the F-105.

In 1981 he became the Chief of Maintenance for the 184th TFG. Under his leadership and management techniques, the 184th experienced a rise in flyable aircraft and soon met all the daily flying requirements.

In early 1983 he became the Deputy Commander for Operations, in which position he oversaw all flying operations. In this capacity he was responsible for all F-4D training, including the F-4D Fighter Weapons School for the entire Air National Guard, Air Force Reserve and Active Duty Air Force units. In March of 1984 Col Sykes led a 12-ship package of F-4’s on a classified deployment to Thumrait, Oman. This was the first-ever deployment of an Air National Guard unit east of the Suez Canal.

Consequently, in 1984 Sykes was selected to represent the Air National Guard at Tactical Air Command (TAC) Headquarters at Langley AFB, Virginia, as the ANG Advisor to the Commander. In 1986 he was called back to Kansas to assume command of the 184th Fighter Group. He held this position for over six years.

During his time at the 184th and after his retirement he played an active part in the Wichita business community as a business owner, board member of the Freedom First Federal Credit Union, board member for the Rose Hill School District, board member for the Quivira Council of the Boy Scouts, and as a board member for the First Presbyterian Church and Wichita Wagonmasters.

He completed a Master of Science in Business Administration at Wichita State University in 1991. He was a member of the 1988 class of Leadership Kansas. In his retirement he has pursued recovery efforts for three of his fellow pilots shot down in Vietnam, finding one of them at this point with the remains recovered, returned, and buried in Arlington Cemetery. He is the author of The Patch and the Stream Where the American Fell, which details his efforts at the recovery of his friend and roommate.

He and his wife, the former Mary K. Bartz of Suring, Wisconsin, recently celebrated 57 years of marriage. From this marriage came four children: Bartz, Jennifer, Ezra, and Amanda. They have fourteen grandchildren.

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail.

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail.

He began his military career by enlisting in the Kansas Army National Guard in 1963. He attended basic and advanced individual training at Ft. Sill, OK in the spring of 1964 and was trained as a Field Artillery Operations and Intelligence Assistant with specialty code 152.10. In May of 1968 he was mobilized with the battalion as a member of Headquarters Battery in Hiawatha, Kansas. While serving at Fort Carson, CO with the battalion he was promoted to Staff Sergeant.

Upon return from active service, SSG Haeffele was hired as a fulltime Guardsman with HHB, 130th FA and assigned as a Personnel NCO. In 1972, recognizing his leadership talents, the battalion reassigned him to a firing battery in order to become proficient in battery field artillery operations. He served as both the Gunnery Sergeant and Chief of Firing Battery, as well as Battery First Sergeant.

He returned to the HHB in 1982 as the Operations NCO. Equally, if not more important, was his role in standing up the Nuclear Training Program within the battalion. This meant becoming qualified in Communications Security, Nuclear Surety, and working closely with the Active Army training teams to establish the Technical Operations teams at Battery level.

He left the technician workforce in 1988, but returned in 1989 as a member of the Active Guard and Reserve Program (AGR). He served the remainder of his career as the fulltime Operations NCO and was instrumental in developing the training program for the transition of the battalion from eight-inch to Multiple Launch Rocket System.

In retirement he continued serving the 130th FA Regiment as historian, his City of Hiawatha as a City Council member, and the Kansas National Guard as an employee of the United States Property and Fiscal Office for Kansas.

His military awards include the Meritorious Service Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, Army Commendation Medal with 2 Oak Leaf clusters, Army Achievement Medal, Army Reserve Components Achievement Medal with four Oak Leaf Clusters, the National Defense Service Medal with Bronze star Device, the Armed Forces Reserve Medal with Numeral “2” Device, and many others.

Educational achievements include an Associates of Arts Degree from Highland Community College, a Bachelor of Science from Friends University, and a Master of Science in Management from Baker University.

Darrel married Sanda May Carter of Hiawatha in June of 1966. Together they had three children—Cherie (Robert) Herlinger, Traci (Calvin) Weibling, and Michael (Michelle) Haeffele. They have five grandchildren and eight great grandchildren. Sandra departed the earth in April of 2018.

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law.

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law.

He enlisted in the 250th Ordnance Company, Kansas Army National Guard, at Belleville, Kansas on September 9, 1965, attending Basic and Individual Training at Ft. Leonard Word, Missouri. He was assigned as an Auto Repairman in Company D, 169th Support Battalion, at Belleville, Kansas, and was mobilized with the unit as part of the 1968 mobilization of the 69th Infantry Brigade (Separate) for the Vietnam War at Ft. Carson, Colorado. Released from Active Duty in 1969, he served as a Repair Foreman in Company D, 169th Support Battalion at Belleville, Kansas. In 1970 he became an Auto Repairman Inspector in Company D, 169th Support Battalion at Marysville, Kansas, then Motor Sergeant and First Sergeant in that unit and in Battery C, 2nd Battalion, 130th Field Artillery, reorganized at Marysville, Kansas.

In 1979 he became a Supply Accounting Technician in Headquarters and Headquarters Detachment, 169th Support Battalion, and was promoted from First Sergeant to Chief Warrant Officer Two (CW2) on December 19, 1979. In 1982 he transferred to Headquarters, State Area Command, where he served as the General Supply Technician, including a 3-year tour in the Active Guard & Reserve (AGR) as a Property Book Technician. He was promoted to the rank of Chief Warrant Officer Five (CW5) on April 5, 1996. He completed his career on February 26, 2006 as the Quartermaster Policy Action Officer in Headquarters, State Area Command.

He served most of his military career as a Civil Service Technician in the Kansas Army National Guard, except for the three-year AGR tour in 1987-1990. He began his fulltime career as an AST (Administrative Supply Technician) at Marysville in 1970, later serving as a General Supply Specialist, Examiner, Management Analyst, Supervisory Supply Technician, and Auditor for the U. S. Property and Fiscal Office (USP&FO).

During his career he completed a variety of military and civil service courses which qualified him for ever-increasing responsibility. These courses included The Army Maintenance Management System, the Administrative Supply Technician Course, the Joint Auditor Training School, NCO courses, Logistics Courses, the Kansas Army National Guard Supply Sergeant School, the Warrant Officer Senior Course and Warrant Officer Senior Staff Course, the U. S. Senior Auditor School, Electronic Mail Training, the Fiscal Law Course, and over twenty audit and internal review courses.

His awards and decorations during his military career included the Legion of Merit, Meritorious Service Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, Army Commendation Medal (6th Award), Army Achievement Medal with 2 Oak Leaf Clusters, the Good Conduct Medal, the Army Reserve Component Achievement Medal with 7 Oak Leaf Clusters, the National Defense Service Medal with Bronze Star, the Armed Forces Reserve Medal with 3 Devices, the Army Service Ribbon, the Kansas National Guard Service Medal with 6 Sunflower Devices, the Kansas Emergency Duty Service Ribbon, and a Certificate of Recognition for the Cold War.

He was named the Warrant Officer of the Year in 2005, received the Kansas National Guard Medal of Excellence, received the Distinguished Performance Award of The Adjutant General of Kansas, and was inducted into the Artillery Order of St. Barbara. He received the U. S. Army Internal Review Award of Merit in 2002, and was one of four nominees for the National Guard Auditor of the Year Award in 2003.

He served as President, Vice President, Membership Chairman, and Board Member of the National Guard Association of Kansas. He is a Life Member of the National Guard Association of both the United States and Kansas and a 53-year member of the American Legion. He has served in many capacities in Our Savior’s Lutheran Church in Topeka, including chair of the Property, Social Ministries, and Audit Committees. He has served as a volunteer for “Communities in Schools,” as an Election Poll Worker, and as a blood donor with over 22 gallons given. He is a member of the Museum of the Kanss National Guard and has led the Museum audit. He has provided pre-mobilization training for the 170th Maintenance Company; the 169th Support Battalion; the 891st Engineer Battalion; the 2d Battalion, 137th Infantry; and the 2d Battalion, 130th Field Artillery.

He has supported Emergency Duty missions in Blue Rapids, Marysville, and Greenleaf, Kansas, and assisted in providing equipment and personnel for many Veterans Day, Memorial Day, and local community celebrations.

He is married to his wife Sandra, and they have two children—Kevin and Corby—and three grandchildren.

Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968.

Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968.

He began his long and distinguished military career by enlisting in the Kansas Army National Guard in 1965. He began his fulltime military technician career in 1968 in Organizational Maintenance Shop #1 at Norton, Kansas. He was promoted through the enlisted ranks, attaining the rank of Master Sergeant before earning an appointment as a Warrant Officer in 1991. In 1992 Ron was selected as the Armament Supervisor at the Maneuver Area Training Equipment Site on Ft. Riley, Kansas. He then moved his family to Manhattan, Kansas. He reached his military mandatory retirement age in 2006, and retired at the rank of Chief Warrant Officer Four, with 40 years, 11 months, and 3 days of service to his nation.

His military career was exclusively in the Kansas Army National Guard. He progressed in rank in Headquarters & Headquarters Company, 110th Ordnance Battalon, Norton, Kansas, starting as a cook in 1965 and culminating as the Battalion Motor Sergeant in 1979. In 1979 he was assigned as the Maintenance Operations Supervisor for the 287th Maintenance Battalion, serving in this role until his Warrant Officer appointment in 1991, when he was assigned to the 174th Supply and Service Battalion as a 915 Series Maintenance Support Technician. In October of 1991 he transferred to the 170th Maintenance Company, where he served in numerous assignments until 2002. During this period he transitioned to a 913 series Armament Repair Technician. In 2002 he transferred to the 174th Ordnance Battalion, terminating his military career in Joint Force Headquarters, in 2006.

During Ron’s military career he was selected to evaluate Cold War Era equipment stores in Germany, prepositioned equipment designed for issue to rapidly-deploying Army units. His evaluations resulted in triaging this equipment’s return to the continental Untied States for repairs to be issued to Army units. As a result, Kansas was selected to be a major repair site under a program called Return Equipment from Europe, or RETROEUR, located on Ft. Riley. The RETROEUR program later metamorphosed into the Readiness Sustainment Maintenance Site. Both programs employed hundreds of Kansas and contributed many millions of dollars into the Kansas economy. After achieving his military retirement, Ron continued his service to the National Guard and Kansas as the Assistant Site Foreman at the Kansas Readiness Sustainment Maintenance Site, Ft. Riley, until he retired from this position in 2015.

He participated in a Foreign Military Sales project for Portugal in 2002, and was the project manager in rebuilding M-109A3 howitzers for them. The success of this project resulted in a good reputation for Kansas that led Kansas to become active in the national maintenance program.

His military awards include the Legion of Merit, the Meritorious Service Medal with 2 Oak Leaf Clusters, the Army Commendation Meal with 2 Oak Leaf Clusters, the Army Achievement Medal with 3 Oak Leaf Clusters, the Army Reserve Components Achievement Medal with Silver Oak Leaf Cluster, the National Defense Service Ribbon, the Armed Forces Reserve Medal with 4 Hour Glass Devices, the NCO Professional Development Ribbons with 3 Devices, the Army Service Ribbon, the Army Reserve Components Overseas Training Ribbon, the Kansas Army National Guard Commendation Medal, the Kansas National Guard Achievement Ribbon, the Kansas Emergency Duty Ribbon with 2 Sunflower Devices, and the Kansas National Guard Service Medal with 3 Sunflower Devices. He was also a recipient of the Kansas Army National Guard Recruiter Badge, was selected as the 1999 Kansas Warrant Officer of the Year, and was a recipient of the Ordnance Order of Samuel Sharp.

He completed numerous courses at Colby Community College, the Kansas Technical Institute, and the National Guard Bureau, and earned his Associate of Arts Degree in General Studies from Barton County Community College.

He maintained active memberships in the National Guard Association of Kansas and the United States, the Enlisted Association of the Kansas National Guard, the Museum of the Kansas National Guard, and the American Legion.

Ron married Diane Smith, the absolute love of his life in Norton on September 11, 1966. They made their home in Norton, then Manhattan, Kansas. They raised two sons, Mike and Mark, Ron was a dedicated family man and always actively supported family activities. He and Diane were church youth leaders and enjoyed car clubs. He was a Scout Master for both Cub Scouts and Boys Scouts, and served as a Little League baseball coach. He enjoyed a variety of activities from meticulous yard care to any outdoor activity and work on and restoring numerous cars. His greatest love was spending time with his family, and doing absolutely anything for his wife, children, and grandchildren.

Ron departed this earth on June 23, 2019, leaving his widow, Diane, who still resides in Manhattan, Kansas, as well as two sons, Mike Mullinax of Silver Lake, Kansas and LTC Mark Mullinax of Wamego, Kansas.

CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist.

CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist.

Upon completion of Technical Training, she received a permanent change of station (PCS) to Aviano Air Base, Italy, where she served for four years. She ended her tour of duty as the NCOIC of the Alert Dining Facility. In 1983 she transferred to McConnell AFB, Kansas and was the Dining Hall Shift Leader until retraining into the Education and Training career field which led to her assignment as the Unit Training Manager for the 384th Security Police Squadron, McConnell AFB.

In 1988 she was selected to be the On-the-Job (OJT) Advisor for the 3753rd Field Training Detachment, affording her the opportunity to conduct OJT courses for Air Force, Air National Guard, and Air Force Reserve personnel. It was during this duty assignment that she met General Tod Bunting (then Major Bunting), who encouraged her to consider the Kansas Air National Guard as one of her future career options.

In 1991 she transitioned to the Kansas Air Guard and served s the NCOIC of the Mission Support Squadron for the 184th Fighter Wing, until accepting an AGR position and retraining into the medical career field as a Health Systems/Aeromedical Technician. While assigned to the Clinic she was selected as NCO of the Year and was nominated as one of the twelve Most Outstanding Airmen for the Air National Guard.

In 1994 she became the Logistics Group Training Manager for the 184th Bomb Wing, where she supervised two personnel and served until 1998. Upon the addition of the Wing First Sergeant position, she was encouraged to apply and accepted the First Sergeant position for the 184th Aircraft Generation Squadron, the largest squadron in the wing. In this position she was blessed to serve the members and families of the 184th Aircraft Generation Squadron and considers it the highlight of her military career. She felt that helping tos ensure the overall well-being of the enlisted men and women was the career field for her. She served in this position from October, 1995 to February, 1998.

While attending the Senior NCO Academy at Gunter AFB, Montgomery, Alabama, she had the opportunity and pleasure to meet the 6th Command Chief Master Sergeant of the Air National Guard, CMSgt Ed Brown, who encouraged her to apply for the Air National Guard First Sergeant Functional Manager position at the U. S. Air Force First Sergeants Academy at Maxwell AFB, Alabama.

From 1998 to 2001 she represented the Air National Guard at the USAF First Sergeants Academy during which time she was the course director and curriculum manager and taught Air National Guad personnel how to be effective and successful first sergeants. She served in this position until being selected as the 8th Command Chief Master Sergeant of the Air National Guard in June of 2001.

During her tour as the Command Chief Master Sergeant of the Air National Guard (2001-2004) she had the opportunity to serve the men and women of the Air National Guard during the September 11/9-11 attacks on the United States. The effort to assess the overall health and well-being of the Air National Guard enlisted corps and their families required travel to over 47 states and territories and nine countries, another highlight of her military career. She retired in 2006 as the Command Chief Maser Sergeant of the Air National Guard.

Her awards and decorations include the Legon of Merit, Meritorious Service Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, Joint Service Commendation Military Ribbon, Air Force Commendation Medal with 2 Oak Leaf Clusters, the Air Force Achievement Medal, the Kansas Outstanding Airman Ribbon, the Air Force Good Conduct Medal with 4 Oak Leaf Clusters, the Air Reserve Forces Meritorious Service Medal with 1 Oak Leaf Cluster, and the National Defense Service Medal.

After serving 26 years in the USAF and Air National Guard she continued to serve her community by becoming an Air Force Junior ROTC Instructor at Northwestern High School in Baltimore, Maryland and Central High School in Capitol Heights, Maryland (2004-2011). In 2011 she began a graduate program in Education and Training with an emphasis on school counseling. In 2013 she was hired to be the School Counselor at Piccowaxen Middle School, Newburg, Maryland, and then McDonough High School, Pomfret, Maryland, where she currently works as a school counselor and department chair. In 2016 the Board of Education and Citizens of Charles County, Maryland, recognized her unusual abilities and her demonstrated exemplary performance in her capacity as School Counselor.

She is a graduate of Excelsior College, Albany, New York with a Bachelor of Science Degree in Psychology and George Washington University, Washington, D. C., with a Master of Arts Degree in Education and Human Development with an emphasis in School Counseling.

During her career she volunteered in many Wichita community activities, as Administrator for Newcomers for the Spirit of Faith Christian Center, with JROTC cadets for community fundraisers following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, in Community Safety Programs in Capitol Heights, Maryland, and as a team mom for her son’s track and field team. She is a Life Member of the Enlisted Association of the National Guard of the United States and the Air Force Sergeant’s Association.

She is married to Anthony Benton, and they have three children–Terrell, Tamika (Jason) McCormack, and Tristan, and seven grandchildren.

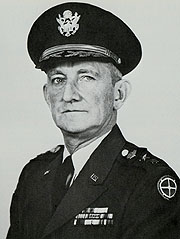

Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas.

Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas.

Born and raised in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, General Small received a Bachelor of Arts in History from Kansas State University in 1969, and a Juris Doctorate degree from the Washburn University School of Law, Topeka, in 1972.

He was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant through the Reserve Officer Training Corps program at Kansas Sate University on June 1, 1969. He was promoted to First Lieutenant in September 1972 and completed the Field Artillery Officer Basic Couse at Fort Sill, Oklahoma in December of that year. From December 1972 to March 1979, General Small was in the U. S. Army Reserve. In March of 1979 he began his career in the Kansas Army National Guard, serving as a State Area Command (STARC) Operations and Training Officer, Executive Officer, Civil-Military Operations Officer, Staff Judge Advocate, Judge Advocate, and Senior Military Judge. Along the way, he also completed the Field Artillery Advanced Course, the U. S. Army Command and General Staff College (1979), the Judge Advocate General Basic and Advanced Courses, and the U. S. Army War College (1994).

In June of 1990, General Small became the Staff Judge Advocate for Kansas, a position he held until becoming the Deputy Commander of STARC in October of 1998. He held the position of Kansas Judge Advocate General under appointment of the Governor from May of 1984 until May of 1999. He was promoted to Brigadier General in July 2000. He retired as The Adjutant General of Kansas on January 4, 2004.

His awards include the Legion of Merit, Meritorious Service Medal, the Army Commendation Medal, the Army Reserve Components Achievement Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, the Armed Forces Reserve Medal, and the Army Service Ribbon.

General Small maintained a private law practice in Topeka, Jonathan P. Small, Chartered, for over 37 years, was Kansas Asst. Attorney General from 1973 to 1978, and was Deputy Kansas Attorney General from 1978 to 1979. He has been a member of the Kansas and American Bar Associations and the American Legion, has been actively involved in the National Guard Association of Kansas, and provides ongoing support in the formation and improvement of the Museum of the Kansas National Guard.

He has served as Chairman and Board Member for the State of Kansas Military Board for 37 years, served for ten years on the Board of Directors of the Great Overland Station, Topeka, and has served as Scoutmaster, member of the Council Executive Committee, and as Council President of the Boy Scouts of America, Topeka.

General Small and his wife, Georgia Anne, reside in Topeka. Their son, Arron, and his wife, Cathy, teach at Purdue University, and their daughter, Jennifer, and her husband, Seth, live in Jefferson City, Missouri.

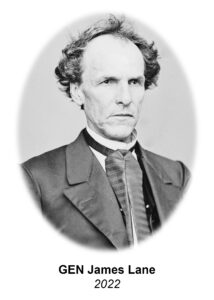

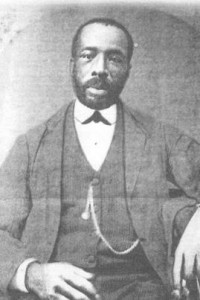

General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas.

General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas.

General James H. Lane was born in Lawrenceburg, Indiana on June 22, 1814, he practiced law, beginning in 1940 at the age of 26. During the Mexican-American War, he commanded the 3rd and 5th Indiana Regiments. He was a U. S. Congressmen form Indiana from 1853 to 1855, where he voted for the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

He relocated to the Kansas Territory in 1855, and quickly became involved in the abolitionist movement, He was often termed the commander of the Free State Army (the Red Legs or the Jayhawkers), a major Free Soil military group. In 1855 he was the first president of the convention that drafted the anti-slavery Topeka Constitution. In 1858, Lane shot and killed a man in a land dispute in Lawrence, but was acquitted in a trial which kept him from participating in the convention drafting the Wyandotte Constitution, later the official constitution of Kansas. In 1861, the Free Soilers succeeded in getting Kansas admitted to the Union as a free state. Lane was elected as the state’s first U. S. Senator, and re-elected in 1865.

During the Civil War, in addition to serving in the Senate, Lane formed a brigade of “Jayhawkers” known as the “Kansas Brigade,” or “Lane’s Brigade,” composed of the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Kansas Volunteers. He commanded the force in action against pro-southern General Sterling Price in the Battle of Dry Wood Creek in Missouri. Lane lost the battle but then stayed around to attack pro-Southern places elsewhere in Missouri. General John C. Fremont ordered Lane to “make a demonstration along the Kansas-Missouri border with his Jayhawkers.” Lane acted gladly, raided the village of Morristown, burned it and swept a wide path of pillage, arson, and murder through the Missouri territory six miles wide and fifteen miles long. His raids culminated in the sacking of Osceola. For this he was criticized severely by Gen. Henry Halleck, Commander of the Dept of Missouri.

On Dec. 18, 1861, Lane was appointed Brigadier General of volunteers, but, because he was still a U. S. Senator, this was questioned, but, after further consideration, was upheld. On October 27-19, 1862, he recruited the 1st Regiment of Kansas Volunteer Infantry (Colored), which debuted at the Skirmish at Island Mound. They were the first African-Americans to fight in the war, and in their first action, 30 of their members defeated 130 mounted Confederate guerrillas.

Lane was the target of Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence, Kansas, on August 21, 1863, in retaliation for some of his actions in Missouri. Though he was in residence in Lawrence at the time, he was able to escape the attack by racing through a nearby ravine. In 1864, when Confederate Gen. Sterling Price invaded Missouri, Lane was a volunteer Aide-de-Camp to Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, commander of the Army of the Border. Lane was with the victorious Union forces at the Battle of Westport in Kansas City.

He was re-elected to the United States Senate from Kansas in 1865, but on July 1, 1866, shot himself as he jumped from his carriage in Leavenworth, Kansas, probably because of his depression over having been charged with abandoning his fellow Radical Republicans and accusations of financial irregularities. He died ten days later, and Edmund G. Ross was appointed to succeed him in the Senate.

Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years.

Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years.

He was born, raised, and spent his life in St. Marys, Kansas, where he farmed, raised his family, was involved in the seed business, and served his church, Immaculate Conception Catholic Church, and his family over his lifetime.

He enlisted in Headquarters Detachment, 174th Military Police Battalion in St. Marys, KS on March 16, 1953, where he served as Mail Clerk and Unit Supply Sergeant. When the unit was reorganized as Company C (-), 2d Battle Group, 137th Infantry, he became a Light Weapons Infantryman, and by 1962 was a Platoon Sergeant in the unit. When his unit was re-organized in 1963 following inactivation of the 35th Infantry Division, his unit became part of the 69th Infantry Brigade (Separate). He then served as Acting First Sergeant at St. Mary’s, as well a Platoon Sergeant of the 69th Brigade Military Police.

In 1968 he was mobilized with the 69th Infantry Brigade and sent to Fort Carson, CO, where he also served as Acting First Sergeant of the 5th Infantry (Mechanized) Police Company and Operations Sergeant of the Provost Marshall Section. For his great work in these assignments he was given an Army Commendation Medal from the 5th Mech Division. Following de-mobilization on December 12, 1969, he returned to duty with the 69th Infantry Brigade (Separate), until it was re-organized as the 69th Infantry Brigade, 35th Infantry Division in 1984, serving in the capacities of Intelligence Sergeant and Operations Sergeant. He was promoted to the rank of Sergeant Major E-9 on January 4, 1982. In 1988 he participated in overseas training with V Corps in Germany, for which he received a letter of commendation.

In the early 1990’s he served as Operations Sergeant Major in Headquarters, State Area Command, and as the Sergeant Major for the G-1 Personnel Section. He participated in many Readiness for Mobilization exercises, was a key leader in the Wolf Creek Nuclear Operating Station exercises, and was involved in the assignment and training of senior NCO personnel in the Kansas Army National Guard. He was a graduate of Advanced and Senior NCO Courses.

He retired on September 17, 1995 with over 41 years of service. His awards included the Legion of Merit, Army Commendation Medal (3rd Award), the National Defense Service Ribbon, the Army Reserve Components Medal, the Armed Forces Reserve Medal, the Army Achievement Medal, the Army Reserve Components Overseas Training Ribbon, the NCO Professional Development Ribbon, the Kansas National Guard Service Medal w/Sunflower Devices, and the Kansas Emergency Duty Ribbon.

He was a lifelong member of the Immaculate Conception Catholic Church in St. Marys, Kansas, serving in many leadership capacities in the church and Knights of Columbus. He was a leader in the Future Farmers of America, the Farmer’s Union Cooperative in St. Marys, the Rossville American Legion, and the St. Marys Veterans of Foreign Wars. He was the face of the Kansas National Guard in the St. Marys community for many years, filling the role with enthusiasm and integrity.

He was married to his high school sweetheart, Patricia Pollard in 1955, and they shared 63 years together. To the marriage was born five sons, Joseph T., Jr. (Deceased), Brad, Jim, Mike, and Jeff, and one daughter, Tricia. He and his wife celebrated 17 grandchildren and 10 great grandchildren. He passed away on April 28, 2019, and was buried in Mt. Calvary Cemetery at St. Marys, Kansas.

Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

On December 10, 1966, he joined the Kansas National Guard’s Headquarters Battery, 1st Battalion, 127th Field Artillery in his hometown of Ottawa, Kansas. He served in that unit for 36 years, retiring as a Master Sergeant E-8 on December 9, 2002. He served as the Battery Clerk, Legal Clerk, Intelligence Sergeant, Personnel Staff NCO, First Sergeant for Headquarters Battery, and Battalion Operations Sergeant during that time.

He served as the fulltime 1st Battalion, 127th Field Artillery Operations Sergeant as an Army National Guard Technician during much of that time. In that position he developed and implemented training plans for all batteries in the battalion, ensured effectiveness of unit training at each Annual Training Period, successfully passed a variety of tests and evaluations, and was instrumental in developing the plan for and fielding the Paladin 155mm Self-propelled Howitzer when his unit became the first in the country to field that weapon.

His awards and decorations during his distinguished 36-year career included the following: Meritorious Service Medal (2d Award), Army Commendation Medal, Army Achievement Medal (2d Award), Armed Forces Reserve Medal (2d Award), Army Reserve Components Achievement Medal (7th Award), National Defense Service Ribbon, Army Service Ribbon, NCO Proficiency Development Ribbon (3rd Award), Recruiting Badge, Kansas National Guard Service Ribbon (w/3 Sunflower Devices), and the Kansas National Guard Commendation Ribbon (2d Award).

During his career in the Kansas National Guard, the 1st Battalion, 127th Field Artillery was not called to active Federal Service. However, he was instrumental in fielding and training many Artillerymen and Kansas Guardsmen who were later mobilized for the Global War on Terrorism, and in ensuring mobilization readiness for countless soldiers during that period. For much of his 36 years in the Guard, he was the well-known face of the Guard in the Ottawa community in the long tradition of the citizen-soldier. His leadership and mentorship of soldiers, junior NCO’s, and junior officers was exemplary and a model for others to follow. His imprint has been felt on both individual soldiers and the Guard both during his career and after his retirement.

He served for over 20 years as a member of the Board of Directors of the Museum of the Kansas National Guard, and from March of 2002 until his death in 2019 as Secretary to the Board of Directors (over 17 years). He also maintained the Museum’s Facebook page and chaired the Museum Finance Committee, which managed the Museum’s Trust Account.

He served both as President and as Executive Director of the Enlisted Association of the National Guard of Kansas (EANGKS). On the national level of the Enlisted Association of the National Guard of the United States (EANGUS) he was Chairman of the Finance Committee and the By-Laws Committee, as well as Director for Area Four, EANGUS.

He was especially active with Cub and Boy Scouts, serving as a leader in the Ottawa Cub Scout Troop 3118 and Boy Scout Troop 127, promoting memberships, activities, leader recruitment and training, financial support for scouting, and development of scouting campouts, activities, and events. He most recently served as the Community Leader for the organization.

He served as a member and the Treasurer of the Franklin County Historical Society in Ottawa, and as a member of the Kansas State Historical Society. In these capacities, he was instrumental in developing exhibit ideas, exhibits, and promotions to preserve the history of Ottawa and Franklin County.

He was active as a member of the Ottawa and Lawrence Model Railroad Clubs, and was heavily involved in running the Train Room at the Old Depot Museum in Ottawa. In addition, he volunteered with the Franklin County Fair Board, serving in many capacities during the Franklin County Fair and in preparations for it.

MSG Gilroy married Shirley Sullivan, and through this marriage he gained three wonderful step-children. They were later divorced, and on December 5, 1985 he was unified in marriage to Bonnie Kiefer, his surviving widow. From this marriage he gained three stepchildren. Eventually he would see eighteen grandchildren and twenty-six great grandchildren.

He was a lifelong member of the First Baptist Church of Ottawa and an avid Kansas City Chiefs and Kansas University Jayhawks fan. He traveled extensively with his kids and grandkids in his RV throughout much of the United States, loved western movies, and enjoyed playing golf with his friends from the Ottawa community.

Many members of his large family were present at his funeral in the Ottawa National Guard Armory on November 5, 2019. The Armory was nearly full of his family, friends, and extended National Guard family as a fitting tribute to this epitome of a citizen soldier.

COL John S. Foster was selected for induction into the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for exceptional service to Kansas Army National Guard Field Artillery, exceptional service to the communities in which he has lived, and for outstanding leadership in the Kansas Army National Guard.

John S. Foster was born November, 6, 1945 to Ernest A. and Ruth K. (Randall) Foster in Savannah, MO. He was raised and educated in NE Kansas. He graduated in 1963 from Reserve Rural High School in Reserve, KS. COL Foster received a Bachelor of Science in Secondary Education from Kansas State Teachers College at Emporia in 1967 prior to entering the Kansas National Guard. He served as a teacher in the Seaman School District #345, Topeka, and the Perry-Lecompton School District #343.

In February 1970, he enlisted in the Kansas National Guard assigned to HHC, 69th Infantry Brigade in Topeka, KS. He attended the Kansas Army National Guard Officer Candidate School and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in June 1972. He was assigned to Battery B, 2nd Battalion, 130th Field Artillery in Horton, KS as a forward observer. He served in all of the Field Artillery Battery positions in Battery B and Battery A, commanding Battery B from August 1978 through September 1979.

In January 1980, Captain Foster began his full-time National Guard career as the Active Guard and Reserve S-1 of the 1st Battalion, 161st Field Artillery in Dodge City. He later served as the training officer of the 2nd Battalion, 130th Field Artillery in Hiawatha, KS. In 1984-1985, while serving as the Administrative Officer of the 169th Support Battalion, he supervised the relocation of the battalion headquarters from Kansas City to Olathe. He later served as the Administrative Officer of the 174th Supply and Services Battalion in Coffeyville and as the Information Management Officer for the Kansas Army National Guard.

He returned to the field in October 1989 as the Executive Officer, 2nd Battalion, 130th Field Artillery and served in that capacity until August 1994 when he assumed command of the battalion. He was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in October of that year. In August 1997, he returned to HQ STARC as Special Assistant to the Adjutant General (Military) and was promoted to Colonel in March 1999.

COL Foster was a graduate of the Field Artillery Officer Basic and Advanced Courses and the Command and General Staff College. He holds a Master of Science in Systems Management from the University of Southern California.

During his career, COL Foster’s awards included the Legion of Merit, Meritorious Service Medal with oak leaf cluster, Army Commendation Medal with four oak leaf clusters, and the Kansas National Guard Service Medal with two sunflower devices.

He was an inductee into the Kansas Army National Guard Officer Candidate School Hall of Fame and Ancient Order of St. Barbara.

In 1980, he engaged the National Guard Association of Kansas with the concept of establishing the Junior Officer’s committee that was adopted at the state and national levels. COL Foster was appointed as the first Junior Officers Chairman in 1982. He commissioned the Junior Officer of the Year awards that are still presented at the National Guard Association of Kansas annual conference as the Major General Ralph T. Tice Award for Army Company Grade Officer of the Year and the Major General Edward R. Fry Award for Air Company Grade Officer of the Year.

In 1989, COL Foster launched a grass roots campaign to bring the Multiple Launch Rocket System to Kansas. Reconfigured as the High Mobility Artillery Rocket System in 2011, it remains in Hiawatha, KS today and has been employed as one of the most lethal weapons systems on the battlefield in the War on Terrorism.

In the midst of fielding the Multiple Launch Rocket System, COL Foster assisted in commissioning the 130th Field Artillery Regimental room and General’s Walk at the Armory in Hiawatha, KS to capture the legacy of the historic regiment.

COL Foster remained an active community member serving as the Chairman of Faith Lutheran Church, Elks member, Lions member, Emergency medical service volunteer, former board member of the Kansas National Guard Museum, board member of North Central Arkansas Foundation for Arts, board member of Fairfield Bay Community Foundation, and American Legion Commander and Officer.

John is married to Barbara (Guebert) Foster. His sons Chris and Tim Foster served as members of the Kansas Army National Guard deploying in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. John and Barbara make their home in Fairfield Bay, Arkansas.

Chaplain (COL) Terry L. Murray was born on May 14, 1946, in Wichita, Kansas, where he was raised and spent much of his life. He graduated from Wichita South High School and Friends University, Wichita. During his time in the seminary he served at Mount Zion and the Reserve, Kansas United Methodist Churches, as well as the United Methodist Churches in Netawaka, Kansas, and Whiting, Kansas. He received a Master of Divinity degree from St. Paul School of Theology, Kansas City, Missouri, in 1971.

After graduating from St. Paul School of Theology he started his ministry as Associate Pastor of the First United Methodist Church in Manhattan, Kansas, and then at Grace Memorial United Methodist Church in Independence, Kansas. He later served in the Wesley Medical Center CPE program as Chaplain and then as co-pastor of the Haysville United Methodist Church and pastor at Zion United Methodist Church, Central Avenue United Methodist Church, and Grace United Methodist Church, all in Wichita. He was a member of the Kansas West Conference of the United Methodist Church until his retirement in 2006.

The last church Chaplain Murray served before his retirement was an inner-city parish that was about to close its doors when he was appointed there. The church immediately began to thrive under his style of leadership, in which he gave permission and encouragement to those in the church who had good ideas and the ability to bring those ideas to reality. As a result, the church rapidly grew in numbers. It hosted a large day care center and a variety of street fairs and parking lot block parties that brought diverse individuals form the neighborhood together. It also built bridges between the community and the Wichita Police Department.

He was an influential community minister through South Central Wichita Neighborhood programs and several school site councils. He was a member and chaplain for the Downtown Cosmopolitan Club of Wichita. His passions included model railroading and Western US and Civil War history. He also owned a couple of small businesses during his time in Wichita, centered on his passion for trains and model railroading.

Chaplain Murray was accessioned as a chaplain in the Kansas Army National Guard and received a direct commission as a First Lieutenant in 1974. He graduated from the U. S. Army Chaplain Basic Course, the U. S. Army Chaplain Advanced Course, and the U. S. Army Command and General Staff College.

He served as battalion chaplain for the 174th Supply and Service Battalion, Coffeyville, Kansas; as group chaplain for the 331st Medical Group, 89th Army Reserve Command (his only four years in the Army Reserve); and Deputy Chaplain, 35th Infantry Division, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He was promoted to the rank of Colonel in 1996 and appointed the State Chaplain, Kansas State Area Command, Topeka, Kansas. As State Chaplain he had responsibility for the Kansas Army and Air National Guard and Civil Air Patrol.

He was the first state chaplain in the United States to include both Army and Air Guard chaplains and chaplain assistants in joint training, and was responsible for Kansas being the first state to use both Army and Air Guard chaplains together in support of state emergency operations. He also opened Kansas Guard chaplain training to Civil Air Patrol chaplains and saw them as valuable partners and state assets. He led statewide training in Critical Incident Stress Management. He was extremely effective at recruiting chaplains for the Kansas Army and Air National Guard. He fostered cooperation between Kansas Guard chaplains and the newly-established Family Readiness program, a relationship that paid big dividends in soldier/airmen family support and care when the mission of the Kansas Guard expanded to include combat deployments in the years following 9-11.

In 1998 he hosted representatives of the Ukranian National Guard who were seeking to implement a United States military chaplain style ministry in their post-Soviet armed forces which would ensure the exercise of religion by their service members. In 1999 he led a delegation of Kansas National Guard chaplains into Ukraine to meet with senior military, civilian, and church leadership to further explore the American military style of chaplaincy.

Chaplain (COL) Murray retired from the Kansas National Guard in 2004 after 30 years of service. His awards and decorations during his career included the Legion of Merit, the Army Commendation Medal, the Air Force Commendation Medal, the Army Reserve Component Achievement Medal, and the National Defense Service Medal.

Chaplain (COL) Murray passed away on August 28, 2009, with services at West Heights United Methodist Church in Wichita. He was survived by his wife of 42 years, Ann; his son Aaron (Vicki) Murray of Denver, Colorado; his daughter Tara Cunningham of Wichita; his step-mother Jane Murray of Honolulu, Hawaii; stepsister Rosa Mitchell and Chris Cook; step-brother Richard Webster, and three grandchildren, Dane, Lane, and India.

![]()

![]() LTC Charles H. “Chuck” Morrow was born on Nov. 21, 1947 at Ord, Nebraska, where he was raised and graduated from North Loup-Scotia High School, Scotia, Nebraska, in 1966. He attended the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, Nebraska, graduating in 1970 with a degree in Animal Science and Industry. He later attended the pre-veterinary medicine program at Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas.

LTC Charles H. “Chuck” Morrow was born on Nov. 21, 1947 at Ord, Nebraska, where he was raised and graduated from North Loup-Scotia High School, Scotia, Nebraska, in 1966. He attended the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, Nebraska, graduating in 1970 with a degree in Animal Science and Industry. He later attended the pre-veterinary medicine program at Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas.

He completed the Reserve Officer Training Program (ROTC) at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, in May 1970. He was commissioned in the U. S Army and served in the U. S. Army Reserve Control Group from January to April of 1971. He served on Active Duty from April 15, 1971 to June 30, 1975. He completed the Armor Officer Basic Course at Fort Knox, Kentucky from April to June of 1971, then was assigned as the Executive Officer/Commander of Company C, 3d Battalion, 1st Brigade at Ft. Knox. He attended Primary Helicopter School at Fort Wolters, Texas from September 1971 to January of 1972, then additional training at the Aviation Center, Fort Rucker, Alabama.

He was deployed to the Republic of Korea in August of 1972, and served as Section Leader and Asst. Operations Officer for the 128th Aviation Company (AHC) in the Republic of Korea until March of 1974. He was then sent to Germany, where he served as Asst S-2/S-3 Air, 1st Battalion, 2d Infantry, 2d Brigade until November of 1974, when he became the Asst. S-3, 1st Aviation Bn, 1st Infantry Division at Ft. Riley, Kansas.

He was released from Active Duty at Ft. Riley on 30 June 1975, joining the Kansas Army National Guard on July 1, 1975. He was assigned as a Platoon Commander in the 137th Aviation Company in Topeka, then as Field Services Officer and Adjutant of the 174th Supply and Service Battalion at Coffeyville. He returned to the 137th Transportation Company in August of 1979, subsequently receiving assignments as a Platoon Leader (Heavy Helicopter) and Executive Officer in the 137th Transportation Company, until receiving command of the 137th Transportation Company (CH-54A Skycrane) in January of 1985. He later served as State Aviation Safety Officer, Executive Officer and Commander of the 1st Battalion, 108th Aviation, and finally as Army Aviation Support Facility Commander in Topeka. He retired on April 1, 1998 as a Lieutenant Colonel.

In addition to those already mentioned, his many schools also included the Transportation Officer Advanced Course, the UH-1 Instructor Pilot Course, the CH-54A (Skycrane) Instructor Pilot Course, the Aviation Unit Commander’s Course, and the C-12 Qualification Course.

His awards and decorations included Master Army Aviator, the Meritorious Service Medal, the Army Achievement Medal, the Army Commendation Medal (w/2d Award), the National Defense Service Medal, the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal, the Armed Forces Reserve Component Achievement Medal (5th Award), the Armed Forces Reserved Medal (2d Award), the Army Service Ribbon, the Overseas Service Ribbon, the National Guard Service Medal, the KSARNG Distinguished Service Medal, the KSARNG Meritorious Service Ribbon, and the State Emergency Duty Medal (2d Award).

He is a Life Member of Alpha Gamma Nu Fraternity at the University of Nebraska, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the American Legion, the National Guard Assn. of Kansas, and the Kaw Valley Chapter of the Military Officer Assn. He has served in many capacities in the Kaw Valley Chapter of MOAA and as a Board Member and volunteer of the Museum of the Kansas National Guard.

While on active duty he was the only aviator cleared to transport members of the team performing South Korean/North Korean peace talks into and out of Panmunjom for the period December 1973 to March, 1974. He coordinated and managed transfer of CH-54 aircraft from the Kansas Army National Guard to the Nevada Army National Guard while commander of Army Aviation Support Facility #1. He coordinated receipt of UH-1 aircraft and equipment for the KSARNG and managed training for aviator crews for both the UH-1 Huey aircraft and the UH-60 Black Hawk aircraft. He accomplished over 5000 accident-free flying hours while flying both rotary wing and fixed wing aircraft and maintained the 1st Battalion, 108th Aviation at 110% while commanding the unit. He assisted in developing a phased maintenance program for CH-54A helicopters which was adopted worldwide.

LTC Morrow has been active in the Highland Park United Methodist Church in Topeka, serving in many capacities over the years. He has been involved in many state and community emergency operations involving Army Guard aviation; in coordinating aircraft involvement for many drug demand reduction programs in schools and communities, including Red Ribbon events; in providing aircraft for community events; and in supporting Guard family programs.

He is married to Karen Morrow of Topeka. He has two children, Michelle and Bethany, both of Orange County, California. He has two step-children, Dillon M. Dreher (Michelle Albano) of Kansas City, MO, and Lindy M. Brewer (Jeff) of Topeka, Kansas. He has four step-grandchildren, Nolan and Camden Brewer and Jalen Moore of Topeka and Talia S. Dreher of Kansas City, MO.

Captain William A. Smith was born Dec. 30, 1888, in Valley Falls, Kansas. After high school graduation he attended the Washburn University School of Law and was admitted to the Bar as a practicing attorney.

He enlisted with Company B, 2d Regiment, Kansas Volunteer Infantry, on June 22, 1916, serving in Texas along the Mexican-American border. While serving with Company B in Texas he was elected Jefferson County Attorney, while only serving briefly before being mobilized in 1917 for World War I with the 139th Infantry Regiment.

His unit participated in the Meuse Argonne offensive, where they attacked in the Argonne sector and assaulted the German positions. By Oct. 1, 1918, the 139th was relieved after sustaining 65 percent casualties.

On Sept. 27, 1918, the second day of the battle in the Argonne, the going had been tough, and all day long Company B lay pinned in their foxholes, covered with mud and water, with enemy fire too hot to make the slightest advance. They had actually moved ahead perhaps fifty years when an order came for Company B to be part of an attack on the village of Charpentry.

Captain Smith, with mud from head to foot and one shirt sleeve torn off a the elbow, rose to his full stature and, with a forward motion of his hand high above his head, yelled, “Come on men. We’re gonna have a helluva fight.” Down over the hill he went with Company B, those still able to go right at his heels.

On return from his service in World War I, Smith continued a long an distinguished legal career. He was first appointed Assistant Attorney for the Kansas Utilities Commission, followed by Commissioner for the Court of Industrial Relations, before becoming an Assistant Attorney General for the State of Kansas in 1922.

Smith was elected Attorney General of Kansas in 1926 and was the only candidate out of seven to denounce the Ku Klux Klan. He was re-elected in 1928. He then became a Kansas Supreme Court Justice in 1930, where he served for 26 years. He became the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Kansas on Mar. 1, 1956, but only served for two years due to health reasons.

Smith and his wife, Ada, lived near Washburn University, often boarding law students. He passed away on July 22, 1968.

Command Sergeant Major Joe Romans enlisted in October of 1969, serving as a Corpsman with the Marine Corps for four years, followed by two years with the Navy Reserve.

Romans was the first Corpsman to attend the U. S. Marine Corps Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) School at Camp Pendleton, CA in 1971.

He next served with a remote U. S. Air Force Radar Site as a Civilian Medical Technician in Arctic Alaska during the Cold War.

He enlisted in the Alaska Army National Guard Eskimo Scout Battalion in 1982, prior to transferring to the Kansas Army National Guard. He then served for 22 years in the Kansas Army National Guard. During that time, he graduated from every level of the Army Non-Commissioned Officer Education System, culminating with the Sergeants Major Academy.

He served as the NCO in charge of the Kansas National Guard Counter-Drug Special Operations Group, supporting Federal, State, and Local Law Enforcement agencies in counter-narcotics operations. He also served as the lead Instructor and NCOIC of the National Guard Bureau’s Counterdrug Ground Reconnaissance Training School.

Romans served during Desert Shield Desert Storm in 1990-91 as a M1 Tank crewman in the Gulf War. Romans deployed with the 5th Special Forces Group and Seal Team 3 as part of the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force-Arabian Peninsula in Iraq during the surge in 2008.

His many assignments, at every unit level of the Army, culminated as the Command Sergeant Major of the 1st Bn, 635th Armor and as Commandant of the 235th Regional Training Institute NCO School.

During his career he served in the following campaigns or countries: Vietnam Era, Cold War Era, Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm, Operation Joint Guardian, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Kosovo, Macedonia, Japan, Germany, and Korea. He takes great pride in that he earned his Cavalry Spurs (Silver) from the 1st Bn, 635th Armor and his Cavalry Spurs (Gold) from the 3rd Bn, 32d Armor Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, in Desert Storm.

Romans descended from an American Revolutionary War soldier, and is a member of the Sons of the American Revolution.

He pursued a career as an EMT, Paramedic, and Paramedic Supervisor for five years. He lived out one of his dreams in professional motor racing as a race car driver. His service to his fellow citizens continues today as a Jackson County Deputy Sheriff in charge of the school protection program and as a volunteer for the Civil Disaster Relief Organization “Team Rubicon.”

CSM Romans and his wife, Nancy, reside in Hoyt, Kansas, and have four children—Kyle, Debbie, Holly, and Joe, Jr., as well as three grandchildren.

Chaplain (Captain) James A. Naismith was born on Nov. 6, 1861, in Almonte, Canada. He applied to be a Chaplain in the Kansas National Guard in 1916. The motivation for this was the same as that for devising the rules for the game of basketball—to help young people and guide them to their full potential.

After quickly obtaining an endorsement as a Presbyterian minister, Naismith was commissioned as a Captain and Chaplain in the 1st Kansas Infantry Regiment.

Naismith and the 1st Kansas mobilized at Ft. Riley in late June of 1916, and then spent nearly four months at Eagle Pass, Texas on the Rio Grande River where they assisted in keeping the Mexican-American border secure. Naismith’s duties during this time included the traditional roles of a chaplain—conducting services, counseling homesick soldiers, and advising his command on the spiritual needs of the unit. With his expertise in athletics, he organized numerous boxing matches, basketball games, and a baseball league to keep his soldiers occupied during their off-duty time.

The 1st Kansas prepared to return home in October 1916. They were released from Active Duty, and Captain Naismith returned to his duties at the University of Kansas and continued service in the 1st Kansas Infantry.

The 1st Kansas Infantry was mobilized in August of 1917 for World War I and was reorganized into the 35th Infantry Division. Captain Naismith wanted to continue his military service and applied for a commission as a U. S. Army Chaplain. However, he was 55 years old and was not an American citizen, so the option was denied. Naismith found another route by working as a volunteer chaplain for the YMCA.

In September, 1917, the YMCA sent Naismith to France, where he worked as one of the organization’s “overseas secretaries” in the war zone. Based out of Paris, Naismith spent most of his time near the front lines, working to improve the social hygiene of the troops. For his work he was ideally fitted, with his background as a clergyman, medical doctor, athlete, educator, and National Guardsman.

He always considered his time in uniform and his work with the soldiers of the U. S. Army to be among his most significant accomplishments.

Naismith and his wife, Maude, had five children. He passed away on Nov. 28, 1939, and is buried in Lawrence, Kansas.

Colonel Wayne L. Cline was born 10 August 1935, in Neodesha, Kansas. In 1953, shortly after graduation from high school, he enlisted in the Kansas Army National Guard (KSARNG) as a Private 1, beginning the life of military service. He attended Officer Candidate School at Ft Sill, Oklahoma commissioning 21 July 1959. He holds branch qualification in Field Artillery, Engineer, Transportation, and Aviation with broad experience in combat service support, combat support and combat units. His many assignments include Platoon Leader, Rotor Wing Aviator, Flight Commander, Operations Officer, Company Commander, Assistant Logistics Officer, Executive Officer, and Army Aviation Facility Commander.

He commanded one of the five Army National Guard Heavy Helicopter (sky crane) units in the nation. He then was tasked to start Kansas’ first Army Aviation Support Facility (AASF) at Forbes Field and commanded the AASF from 1972 – 1979. He served as AASF Commander from 1972 – 1979 and State Aviation Officer from 1979 – 1990. Wayne was the first full-time instructor pilot for the KSARNG, the first KSARNG aviator to fly helicopters in actual instrument weather conditions, the first rotor wing instrument examiner in the KSARNG, and fielded the first CH-54 Sky Crane company in the National Guard. He implemented a phase maintenance system for CH-54A helicopters, which was adopted world-wide, improving readiness 100%.

Wayne has approximately 10,000 accident-free flying hours, while flying sixteen different types of aircraft. His numerous awards include the Legion of Merit, Army Commendation Medal, State Emergency Duty Medal w/2 Award, and the Award for Army Excellence – the only Kansas National Guard Aviator to receive this award. Wayne and his wife Twila reside in Topeka and have three children, nine grandchildren, and 12 great grandchildren.

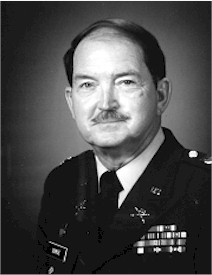

Colonel James E. Trafton was born 10 October 1951, in Nashville, Tennessee, where he attended elementary and high school. In 1971, shortly after graduation from high school, he enlisted in the U.S. Army as a Private, beginning a life of military service. Following initial training he was assigned to a Reconnaissance Platoon in the 1st Cavalry Division in Vietnam. He joined the Kansas Army National Guard where he served ten years as an enlisted man and as a Noncommissioned Officer, reaching the rank of Sergeant First Class. He graduated from the Kansas National Guard Officer Candidate School in 1982 commissioning as an Engineer Officer. He served in various positions including Engineer Platoon Leader, Operations Officer, Assistant Logistics Officer, and Commander, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, all with the 69th Infantry Brigade. On 23 November 2003 he became the Commander, 2nd Battalion, 137th Infantry transitioning from the M113 Armored Personnel Carriers to the M1A1 Bradley Fighting Vehicles. He led the battalion to Baghdad, Iraq serving under the 4th Infantry Division with responsibility for the Joint Visitor’s Bureau and security for the many high-level visitors that passed through Iraq. He was promoted to Colonel in 2006 and began his culminating assignment as the Kansas Army National Guard Strength Management Officer. He was well known as a “Soldier’s Soldier” and a natural leader, providing leadership, counseling, empathy, career advice, and an interest in the lives of his soldiers and their families. Upon retirement after 37 years of military service, he was inducted into the Kansas National Guard Officer Candidate School Hall of Fame. His numerous awards include the Legion of Merit, Bronze Star Medal (2nd Award), Meritorious Service Medal (4th Award), and the Combat Infantryman’s Badge (2nd Award-Star). Jim was married to Theresa for 17 years, had four daughters, and five grandchildren. Colonel James Trafton passed away 5 April 2010 and was buried with full military honors in the Leavenworth National Cemetery, Leavenworth, Kansas.

Chief Master Sergeant Danny M. Roush was born 2 November 1952 in Kansas City, Kansas. He graduated from Tonganoxie High School in 1970 and joined the 190th Civil Engineer Squadron, Kansas Air National Guard in 1973 as an Interior Electrician. He was assigned to the Interior Electric Shop remaining until 1984 rising through the ranks to Master Sergeant. He was selected as the Exterior Electric Shop supervisor serving three years. He was the Squadron First Sergeant from 1987 – 1991. He was the first Squadron member to attend the Air National Guard / Air Force Reserve First Sergeants’ Academy at Keesler Air Force Base, Mississippi. He was selected as the First Sergeant of the 1701st Strat Wing in Kuwait. Upon returning home he was promoted to Senior Master Sergeant and served as the Electrical Superintendent, 190th Civil Engineer Squadron and the Facility Manager 190th Air Refueling Wing. Danny was promoted to Chief Master Sergeant in 1995 and assigned as the Civil Engineer Manager, holding this position until retirement in 2012. He deployments include Kirkuk, Iraq in support of Iraqi Freedom, Camp Justice at Guantanamo, Cuba, and Haiti in support of humanitarian efforts after their earthquake. After serving 39 years in the Kansas Air National Guard he continued serving in the Kansas Division of Emergency Management. His numerous awards include Meritorious Service Medal with 1 Oak Leaf Cluster, Air Force Commendation Medal with 9 Oak Leaf Clusters, Humanitarian Service Medal, Military Outstanding Volunteer Service Award, Kansas Senior NCO of the Year, and Kansas Airman of the Year. Danny is heavily involved in the American Legion Post 125, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and the Museum of the Kansas National Guard. Danny and his wife Carol reside in Lyndon and have two daughters and seven grandchildren.

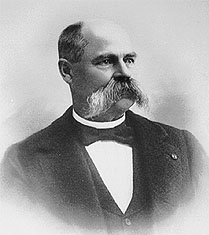

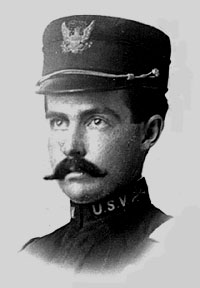

Brigadier General Wilder S. Metcalf was born at Milo, Maine, 1855. He was reared by

his family in Elyria, Ohio. He joined the Co G, 5th Ohio National Guard Infantry on May 6,

1884 at the age of 29. He served in his unit until July, 1886. In 1887 he came to Kansas and was

located in Lawrence, Kansas. He became a partner of Edward Russell in the farm mortgage

business. In 1888 he enlisted as a Private in Co H, 1st Kansas Infantry at Lawrence, Kansas,

rising in rank to Colonel over the next nine years. He was Colonel of the Regiment in 1898 when

the Spanish American War broke out.

He was commissioned a Major in the 20th Kansas Infantry, under Colonel Frederick

Funston. The 20th Kansas was mustered for Federal Service on May 9, 1898 at Topeka. Three

days later they were sent to Camp Merritt, California, at San Francisco. He later moved to

Indiana and steamed for Manila in the Philippines. They arrived and were encamped in the

tobacco warehouses. In 1899 the 20th Kansas was ordered to the front. The regiment advanced

on and was the first to enter Caloocan on February 10, 1899. In March, the regiment swam the

Tuliahan River, captured a blockhouse, and then was involved in the engagements of Malinta

and Maycuayan three days later. Upon Colonel Funston’s promotion to Brigadier General, Major

Metcalf was elected Colonel of the 20th Kansas. He was awarded the Order of Purple Heart in

recognition of being wounded twice.

On September 6, 1899 the war was declared to be over, and the 20th Kansas boarded

transports and steamed for the United States. Upon his return to Lawrence, Kansas, he again

became the Colonel of the First Kansas Infantry, and served until 1915, when , as part of a Civil

war in Mexico, Pancho Villa, a Mexican warlord attached to the 13th U.S. Cavalry. President

Woodrow Wilson ordered the mobilization of the National Guard to assist on the border. Led by

Colonel Metcalf they marched several miles into the desert and established camp. Colonel

Metcalf was appointed a Brigadier General of the National Army on August 22, 1917, and

honorably discharged on May 24, 1918. He was promoted to Brigadier General in the Kansas

National Guard on February 24, 1919.

General Metcalf was a delegate at large to the Republican National Convention in 1900

when McKinley and Roosevelt were nominated. In 1901 he was appointed by President

Theodore Roosevelt as United States Pension Agent in Topeka, Kansas. He was the only person

to hold the office for two terms. In 1909 he was appointed by Secretary of War as a member of

the National Militia Board. In 1916, while serving in the Philippines, he was elected for a seat in

the Kansas Senate. For eighteen years he served as a member of the Lawrence School Board and

for several years as its president.

His fraternal associations included being a Knight Templar and a Noble of the Mystic

Shrine in the Masonic Order. He was a member of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks,

the Army and Navy Club of Washington, D.C. , the University Club of Kansas City, the Topeka

Club, Phi Delta Phi, and Phi Gamma Delta. He also belonged to the Military Order of Foreign

Wars, the Spanish-American War Veterans, the Army of the Philippines, and the Military Order

of Carabas. During his lifetime he was listed in the “Who’s Who in America” listing for several

years.

The National Guard Armory at Lawrence, Kansas is named the Wilder S. Metcalf

Armory.

Brigadier General Charles M. Baier was born in Larned, Kansas in 1942. He grew up on

a farm near Seward, Kansas. After high school, Baier attended Fort Hays State College. In early

1963 the Kansas Air National Guard was recruiting pilots for the 190th Tactical Reconnaissance

Group at the Hutchinson Air National Guard base. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant

in 1963. He trained in the Air Force Undergraduate Pilot training program at Moody Air Force

Base, Georgia. He received his wings on March 28, 1966.

After graduating he returned to Kansas and qualified as a pilot flying the Martin RB-57A.

He was hired by TWA in 1967. His two careers complimented and enhanced each other, as the

basic skills were the same, even though the environment was vastly different. In 1972, the 190th

Tactical Reconnaissance Group received new aircraft, a new mission and a new designation. It

gained Martin B-57G aircraft for precision all weather night bombing and became the 190th

Tactical Bombardment Group. In 1974, they saw another transition to the 190th Defense

Systems Evaluation Group. 1977 brought some of the most significant changes to the 190th.

They became the 190th Air Refueling Group.

In 1980 he became the Commander of the 117th Air Refueling Squadron. In 1984, Baier

became the State Director of Operations at Kansas State Headquarters. In this position he

provided leadership and advice, not only to the 190th, but also to the 184th Tactical Fighter

Training Group in Wichita. Early on the morning of January 16, 1991 the communications

center notified Baier they had received an Immediate Flash Top Secret, “eyes only” message for

him. It was the notification that combat operations would commence the next morning. Desert

Shield was about to become Desert Storm. The pace was hectic for the next weeks. Baier flew

several refueling missions during both Desert Shield and Desert Storm. After several weeks of

intense operations, Operation Desert Storm ended. They returned home in March to a crowd of

over 10,000 people.

During his time as a group commander, Baier encouraged and expanded community

relations and involvement in the Air Guard’s mission and the importance of support of the

community. He was involved with the Chamber of Commerce, Metropolitan Topeka Airport

Authority Board of Directors. Baier was promoted to Brigadier General in the Kansas National

Guard on August 2, 1992. General Baier retired in 1993 after 30 years of service.

His awards include: Legion of Merit-1Oak Leaf Cluster, Meritorious Service Medal, Air

Force Commendation Medal, Air Force Achievement Medal, Air Force Outstanding Unit

Ribbon-1 Oak Leaf Cluster, Combat Readiness Ribbon –6 Oak Leaf Clusters, National Defense

Service Ribbon, Southwest Asia Service Medal-2 Bronze Stars, Kuwait Liberation Medal-

Kuwait, Kuwait Liberation Medal-Saudi Arabia, Aerial Achievement Medal, Air Force Overseas