The 22nd Kansas Volunteer regiment was made up of men who had volunteered for service in the war with Spain. Companies were raised across the state and these were brought together at Camp Leedy, in Topeka. The regiment was mustered into United States service on May 17, 1898. Many of the men reported for duty in their most tattered clothing, as they expected to be issued uniforms in Topeka. The Army, however, refused to issue uniforms until the men shipped out for their next duty post. On May 25 the people of Topeka turned out to see the regiment off as it departed by rail for Camp Alger, Va. Three days later the regiment exited the train at Dunn Loring, Va., and marched to Camp Alger.

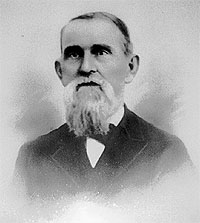

Eventually they were met by an Army staff officer who “marched them something over two miles out of the way over a dusty road, crowded with Army wagons and about sundown pointed out the location chosen for our camps. No one complained of this but when he ordered us to pitch tents within 100 feet of the sinks of a New Jersey regiment we felt that we were imposed upon.” according to Maj. A. M. Harvey, previously the lieutenant governor of Kansas until he joined the Volunteers. He also vigorously complained about the overcrowding of the regiments, the unsanitary conditions and the inadequate water supply.

Pvt. Samuel Adams of Topeka recorded the daily routine as the Army tried to turn civilians into soldiers:

JUNE 1.–Usual program today

First call for Reville, 3:15

Assembly, 5:30

Breakfast, 5:45

Gen’l police of Camp, 6:15

Sick Call, 6:15

School of Soldier, 6:30

Recall from drill, 7:30

Theoretical instruction, 8 to 9:00

Drill School of Co. or Battalion, 9:30 to 11:00

Dinner, 12:00

Guard Mount, 1:30

Instruction in tending wounded, 2 to 2:30

School of Battalion, 3:00

Recall from Drill, 4:30

Supper, 5:30

Dress Parade, 6:00

Tattoo, 9:15

Taps, 9:30

To prepare the Volunteers for service in the tropics the Army vaccinated the men, with the result that a large number of the men became sick from the vaccinations. So few healthy men were available for a regimental dress parade that the reviewing officer told the company commanders to dismiss their squads.

In Cuba on July 1, U.S. forces won battles at El Caney and San Juan Hill, and two days later the Spanish fleet at Santiago, Cuba, was destroyed by the U.S. Navy. At Camp Alger the daily routine dragged on as the troops continued their preparations for the war.

Pvt. Adams recorded in his diary:

JULY 5.–Regular program today. Private Dolby loaded his gun on drill to-day with a blank and when ordered to fire discharged his piece so that the wad went right over the men in the rank a few feet in front. The Second Lieut. was greatly shagrinned by the act and said that his hair was burned. He was so excited that the Captain told Henderson to conduct Dolby to the Guard house where he now is. Dolby did it for a joke and a great joke it was. Cooper & Neff went to town today.

JULY 6.–Regular program again. Drilled on battle line, practiced on firing and making rushes on the enemy. It drizzled some in the morning.

On July 25, Pvt. Ernest Clark was put under arrest by Capt. William Stevenson for writing home “the truth about the relations of the Capt to the Company,” and was fined and jailed. Because of irregularities the case had to be retried on July 28:

“Clark’s trial was very favorable to him. The Captain I hope feels better but honestly I believe he does not. Clark by his last trial rec’d. a fine of two dollars with no imprisonment. The Lieut.-Colonel was so drunk Wed. night that he did not get over the effects in time to preside at the Court Martial. It was probably very fortunate for Clark that he was disqualified. The Lieut. Col’s son in Co. I, was put under arrest, by the lieut. Col. for remonstrating with his father for being drunk. Ritchie and I got a pass to-night to go to Washington to-morrow,” Adams wrote.

Drinking apparently became such a problem that patrols were sent out at night to ferret out moonshiners and bootleggers. Although he was not an official member of the patrols, acting Sgt. Maj. George A. Elliott accompanied several of them. He appears to have put the knowledge gained to good use, for in late July Elliott and Sgt. McManus got drunk, and Elliott wrote himself a pass and left camp with McManus. “The two men proceeded to the home of an inoffensive old man, who lived near the camp and intimidating him with a couple of six-shooters, they stood him in a corner while they ransacked the house. They fired their revolvers several times to show what bad men they were.” For their efforts Elliott and McManus were arrested and put in the guardhouse.

The daily duties of the men included drill, sham battles and guard duty. The hot Virginia summer frequently caused afternoon maneuvers to be called off. Every 24 hours 75 men were detailed for sentry duty around camp; this was more to keep the Kansans in than strangers out. By late July, however, the attraction of the world outside camp would have lessened as the men had been without pay for some time and most of them were broke. The operator of the canteen for the Kansans stopped extending credit to the men, so several companies began issuing passes to allow the men to visit the canteen belonging to the Indiana regiment. Army routine wore on the men, and they began asking for a change of any kind. “They are getting tired of staying about Camp Alger and are anxious to go to Porto Rico. The hope that we will go is becoming stronger each day, and as the last review was before Secretary of War Alger it is being rumored that it meant something.”

In July a typhoid epidemic hit Camp Alger. Within the 22nd 15 men died. Army authorities decided to remove some of the troops to healthier camps, and on Aug. 2, 1898, the regiment began a difficult march to its new camp near Manassas, Va. It did not reach its destination until Aug. 9. Pvts. John Throckmartin and Charles Throckmartin, brothers, contracted typhoid on the march and died on Aug. 25 and Sept. 11, respectively.

Army authorities did not provide adequate rations for the march. One soldier remembered that “After one or two nights of going to bed hungry, getting up a little more hungry and marching a day fairly famished, a crowd of us determined to do a little foraging as our fathers had done before us through that same country.” The men came up with a scheme to get food from local farmers:

We entered a yard surrounding a nice looking house and feebly asked for a drink of water. As we waited for the cup, our actor leaned heavily against the house and emitted a hollow groan that must have struck one as coming from his very soul. Of course the woman–how glad we were it was not a man–asked us what was the matter with our companion and then the whole story of our hardships, our patriotism, our silent suffering and our actual starvation was poured into her sympathetic ears.

You should have seen the result. There were tears in her eyes as she told us to come into the house and get something to eat, according to Adams.

The act was successfully repeated at the next farm, but at their next stop they met failure when what appeared to them to be a plantation house turned out to be the county poor farm. The men left empty handed, but along their way back to camp stole crocks of milk, eggs, chickens and fruit. “By the time we had reached camp we were loaded down and every man in the regiment was our friend.” Theirs was not the only breach of discipline:

… the boys have gotten tired of their slim diet of hard tack, potatoes, onions, ‘Sow bosom’ and Coffee and are scouring the country for everything they can find. They are almost all broke, and so take apples, and chickens and despoil the milk houses of milk and butter. It is reported to-night that they did not stop with smaller damaging. But killed beefs, robbed graves for relics and molested the inhabitants, Adams wrote in his diary.

Soon an armistice was signed between Spain and the United States. For the men of the 22nd the prospect of getting into a shooting war was fading away. The following two weeks were spent in the usual routine of drill, washing clothes, going swimming and trying to duck past the camp guards to visit the locals. Some of the men signed a petition asking for early discharge. On Aug. 26 Adams recorded in his diary that “When McConkey came back from town he brought a Wash. Star which said that the 22nd Kans. would be ordered to Topeka to be mustered out immediately[.] on acct. of same there has been great excitement all evening.”

On Aug. 27 the regiment was moved by rail to Camp George C. Meade in Pennsylvania. The men still performed drill and took their turns at guard duty, but loafing took on more importance than did drill. Finally orders were received for the regiment to move to Fort Leavenworth to be mustered out. The regiment left Camp Meade on Sept. 9 and reached Leavenworth on Sept. 13 where the citizens turned out to welcome them home. The men were given a 30-day furlough, and officially mustered out on Nov. 3, 1898.

In its four months of active duty the 22nd had 16 men die of disease, half of them from typhoid.

(Reprinted from Benedict, Bryce D. “22nd Kansas Spent Frustrating Time in Virginia,” Plains Guardian, June 1998, pp. 18-19.)

22nd Kansas’ Soldiers Accused of Grave Robbing

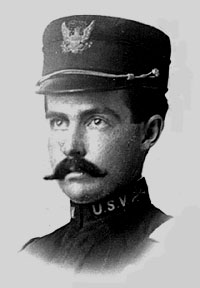

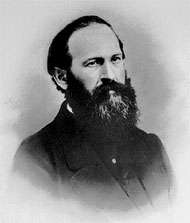

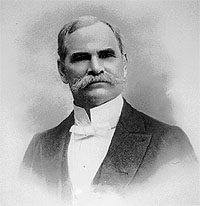

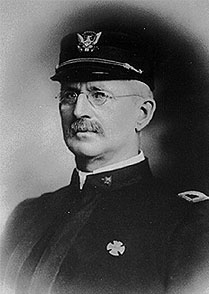

The most infamous charge of grave robbing was made against Capt. L. C. Duncan, the 22nd Kansas Volunteer regiment’s assistant surgeon. He was charged with desecrating the graves of two Civil War Confederate soldiers. Virginia citizens were enraged, and a Fairfax county grand jury returned an indictment against Duncan. The sheriff demanded that Duncan be handed over to him. A General court-martial was soon convened. Charges were served on Duncan at 10:00 p.m. on Aug. 12, [1898] and the trial commenced the following day at 11:00 a.m.

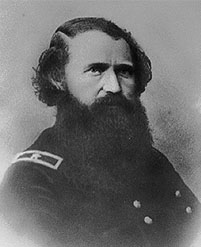

One of Duncan’s defense counsel was Maj. A. M. Harvey of the 22nd, who had been the lieutenant governor of Kansas until he joined the Volunteers. The trial lasted 14 days, but at the end Duncan was found not guilty of the grave robbing charges. However, he was found guilty of “conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline” in failing to arrest enlisted men (not from the 22nd) who had committed the crime.

Duncan was sentenced to loss of rank for two months, to forfeit half his pay for the same period of time, and to be confined to the regimental camp. This sentence was set aside by the convening authority.

That was not the end of Duncan’s legal troubles. Following his court-martial Duncan was arrested by the sheriff of Fairfax County, Va., handcuffed, and confined in the county jail until he could make bail of $1,100. According to Harvey the sentence was only a $100.00 fine.

This was not Duncan’s first brush with charges involving grave robbing. In December 1895 he was a student at the Kansas Medical College in Topeka. Bodies taken from local cemeteries had ended up as cadavers at the medical school.

A public outpouring of anger at the college followed, and the Governor called out two National Guard companies as local authorities feared mob action. Arrests were made of college authorities. Relatives of the deceased threatened to file a suit, and many students, including Duncan, were identified as defendants to be named.

There is no evidence that Duncan had any involvement with the grave robbing or had knowledge that the bodies were stolen.

(Reprinted from Benedict, Bryce D. “22nd Kansas’ Soldiers Accused of Grave Robbing,” Plains Guardian, June 1998, p. 19.)

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law.

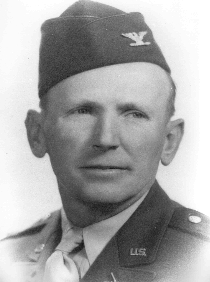

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law. Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968.

Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968. CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist.

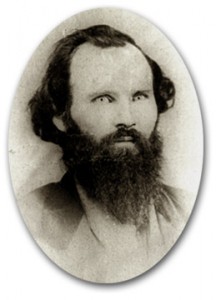

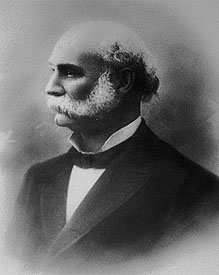

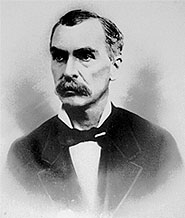

CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist. General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas.

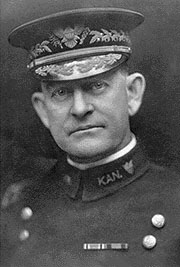

General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas. Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years.

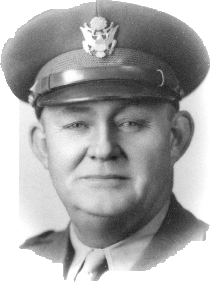

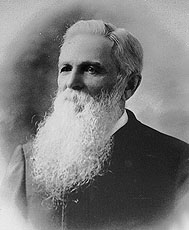

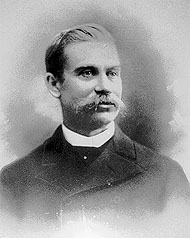

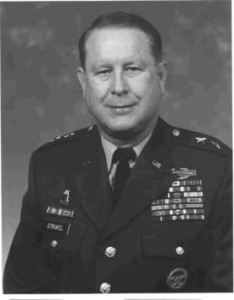

Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years. Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas.

Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas. Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

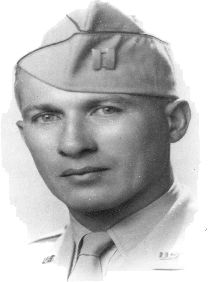

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital. Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.